Intercepted wartime dispatches between Berlin and Tokyo

a summary of a very cool talk I attended

- 6 minsA few weeks ago I attended an awesome presentation. The speaker, Dr. Peter Kornicki from the University of Cambridge, opened with a story about a second year university student who was mysteriously asked to participate in a very, very secret program… to learn Japanese, alongside 29 other handpicked students.

Titled “Stolen Secrets: Intercepting Dispatches between Wartime Berlin and Japan”, this talk offered a very interesting perspective into the Second World War that I had never really given much consideration - namely the apparent shortage of fluent Japanese speakers in the west at the time. There is a video of the entire talk in the link - if you have around 50 minutes to spare, just go watch it! Most of this post is based on my notes and memories and is by no means academic or 100% accurate, and this whole thing is more to jog my own memory than anything else.

Moving on - for some background, the Japanese diplomatic encryption machine, “Purple”, had been broken by American cryptoanalyists in 1940, and by the Russians in late 1941. That same year, the Japanese were alerted by a diplomat at the German Embassy that Purple had very likely been broken, but even then the Japanese continued using the cipher throughout the war.

This meant that even before the complete deterioration of Japanese-American relations in December 1941, American and British cryptoanalysists had been decrypting and translating Japanese diplomatic transmitions, although the Pearl Harbour attack itself was never mentioned in transmissions before the morning of December 7th - a point emphasised by Dr. Kornicki when asked about it by an audience member.

Comparatively speaking, once Purple had been cracked the primary difficulty was actually in translating the decrypted messages. There was an acute shortage of Japanese linguistic talent in Britain especially - unfortunately I couldn’t write down the figure Dr. Kornicki mentioned, but I did manage to scribble this down:

1919 ~ 1939… 3 Japanese language graduates

Some had raised warnings prior to the outbreak of war that this shortage would cause severe problems - what use were decrypted messages, if there were insufficient translators capable of not just translating and interpreting the many thousands of intercepted messages, but doing it quickly enough to save lives?

So began an ambitious British program, of which the character mentioned in the first paragraph of this post was a part of, to teach students - most of which had no prior Japanese experience - to translate decrypted Japanese messages. There was two parts of this - one to decrypt written messages, and “eavesdroppers” to interpret radio messages and conduct interrogations closer to the front line in places like Mombasa, Sri Lanka, and Delhi.

To accommodate the former, a special 6-month course was devised at the SOAS University of London in less than a month. This course focused translating long strings of decrypted romaji, omitting aspects like spoken Japanese. On the side of the course designers was the limited range of words used in the diplomatic transmissions, relatively (compared to the military transmissions) umambiguous volcabulary, talented and devoted students, and a healthy dose of patriotism.

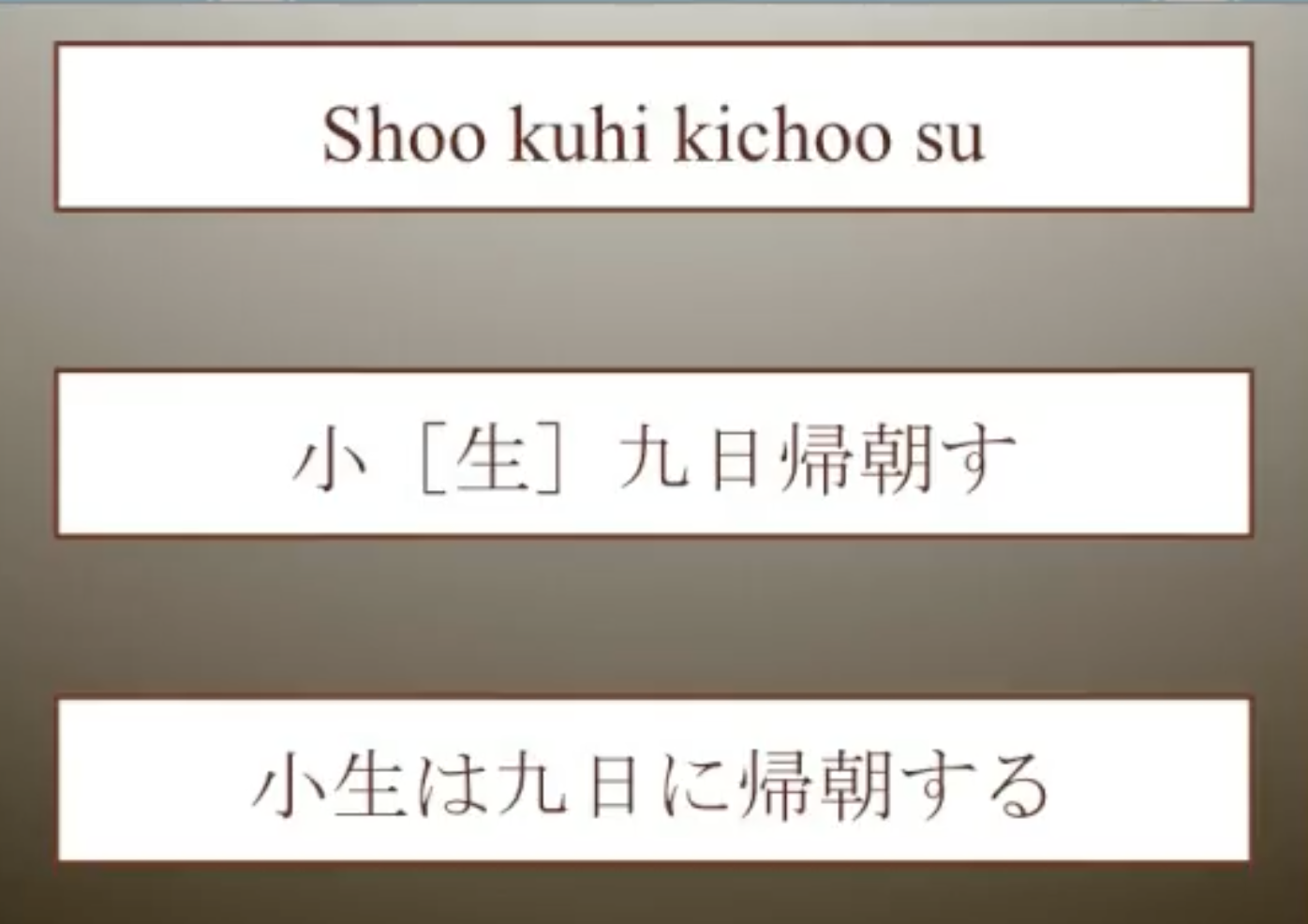

An example of one of their translation tasks, presented to student Patrick Field at the end of his 6 months of studying:

No one in the audience old (and presumably some Japanese) people could answer. Neither could my dad, who has been speaking Japanese for over 20 years by this point, when I sent it to him the next day.

The next slide offered the answer that Patrick Field (correctly) wrote down at the time:

A simple message, it turns out: “I’m going back to Japan on the 9th”. Well.

“For all of us”, Dr. Kornicki admits, “it really is a bit humiliating.”

Dr. Konicki’s talk also focused heavily on the contents of the Japanese ambassador to Berlin Hiroshi Oshima’s dispatches to Tokyo throughout the course of the war. Relayed through Moscow (and later, Beijing), virtually every single one was intercepted by the British along the way. These dispatches numbered up to 600 per year and were sometimes up to 20 pages in length, all of which were rapidly decrypted and translated thanks to the efforts of the students of the aformentioned program.

Hiroshi’s dispatches revealed a man who, partly due to his talent in German, developed a very close relationship with Hitler during his time as ambassador. Without translators and free of any language barriers, the two would often spend hours together discussing the war - discussions that Hiroshi would report back to Tokyo, and unbeknownst to him, the Allies.

Even though Hiroshi was fiercely (though wrongly) optimistic about Germany’s eventual victory in his dispatches right up until the very end - a sentiment he would come to deeply regret as he came to believe he had mislead his country - his dispatches provided invaluable intelligence to the Allies, such as:

- Operation Barbarossa - this was passed to the USSR, albeit in the guise of a mole’s intelligence, but Stalin did not believe it at the time

- Hitler’s expectations of how the invasion of Normandy would play out - this confirmed to the Allies that the deception around where Overlord would take place had been successful

- though the specific location of the German counteroffensive was not revealed, the Ardennes Counteroffensive was hinted at in Hiroshi’s correspondence

- detailed reports about the state of Germany

General George Marshall went so far as to eventually identify Hiroshi as “our main basis of information regarding Hitler’s intentions in Europe”, though Hiroshi never lived to learn the true extent of his role in World War Two - he passed away in 1975, before knowledge of the intercepted dispatches became public.

Most interesting, to me, is what happened to these translators in the wake of the war. Bound to secrecy, many apparently continued their Japanese studies, helping set up programs like UBC’s Asian Studies department and foster positive post-war relations with Japan.

Some time was spent discussing why the translators left the war with such a positive view of Japan and Japanese culture. Dr. Kornicki points out that many of the teachers had spent time in peacetime Japan - a good portion of them were there as teachers, students, or officers working alongside the Japanese Navy prior to the war - so their impressions of Japan were of a Japan at peace. Thus, many teachers shared their genuine interest and respect for Japanese culture, finding time in their rigorous courses to instill that appreciation in their students, who carried that forward to their own students.

I thought that whole aspect was incredibly interesting, especially in regards to how the attitudes of a select few produced such a profound impact on the development of Japanese studies in the west, especially when given the circumstances (being at war and everything), the opposite could easily have been true.

Some positivity really can go a long way.