Building a self-hosted continuous deployment solution

How a team of students designed and created a flexible, Docker-based Heroku alternative

- 12 minsHere at UBC Launch Pad, many of our teams’ projects are web applications. A pretty awesome step in any web application’s development process is when you deploy it for everyone to try out, and we wanted to enable all our teams to get there.

Unfortunately, deployment can be a frustrating task, especially for students with little to no experience setting up applications on remote hosts. Some of these students might also be learning a new framework or programming language as part of their projects, all while dealing with the stresses of a full course load. On top of that, we frequently find ourselves needing to deploy projects to new environments as funds run out or sponsorships end in order to keep projects online.

This was an unfortunate situation — seeing your hard work up and running can be a nice motivation boost, and the ability to gather feedback from fellow students is invaluable. So over the winter, we gathered a small team to develop an in-house tool that would make setting up continuously deployed applications simple and painless, regardless of the hosting provider. We decided to call it Inertia.

This post will briefly outline how Inertia works, the thinking that drove some of its design decisions, and the techniques and tools used to build it.

# 🎨 Design

We set out with a few primary goals in mind:

- minimise the number of steps required to set up continuous deployment

- maximise cross-platform compatibility on clients and servers

- offer an easy-to-learn interface to control deployments

Continuous deployment just means automating the process of updating a deployed project as code changes. To accomplish this, we quickly settled on a simple two-component design: a client-side command line interface (CLI), and a server-side daemon.

A daemon is typically a process that runs persistently in the background— in our case, a tiny server that runs on your remote host, waiting for commands to be delivered to it. These could be HTTP requests from the CLI or WebHook events from GitHub. WebHooks are HTTP POST requests that are sent by “notifiers” — in this case, GitHub — to registered “listeners”, such as the Inertia daemon. This allows Inertia to automatically detect changes to your applications source code and make updates to the project in the background, without requiring manual intervention.

The CLI is a small application that the user downloads to use Inertia. It handles all local configuration and is in charge of sending commands through HTTP requests to the server-side daemon.

# 🐳 Cross-Platform Compatibility

Because we change hosting providers so frequently, an important requirement of Inertia was that it should work on any major OS from any cloud provider.

This is where Docker comes in. Docker is massive open-source containerization project that has really blown up in the recent years, and the flexibility of containerization has proved incredibly useful and scalable. Netflix, for example, deploys up to half a million containers every day! The Docker website provides a nice introduction to the concept, emphasis mine:

A container image is a lightweight, stand-alone, executable package of a piece of software that includes everything needed to run it: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries, settings. […] containerized software will always run the same, regardless of the environment.

Since a single Docker container can run anywhere that Docker runs we bypass the problem of cross-platform support by simply deploying the Inertia daemon from a Docker image. On top of that, through DockerHub — Docker’s online image repository service — we don’t need to worry about managing distribution of the daemon either.

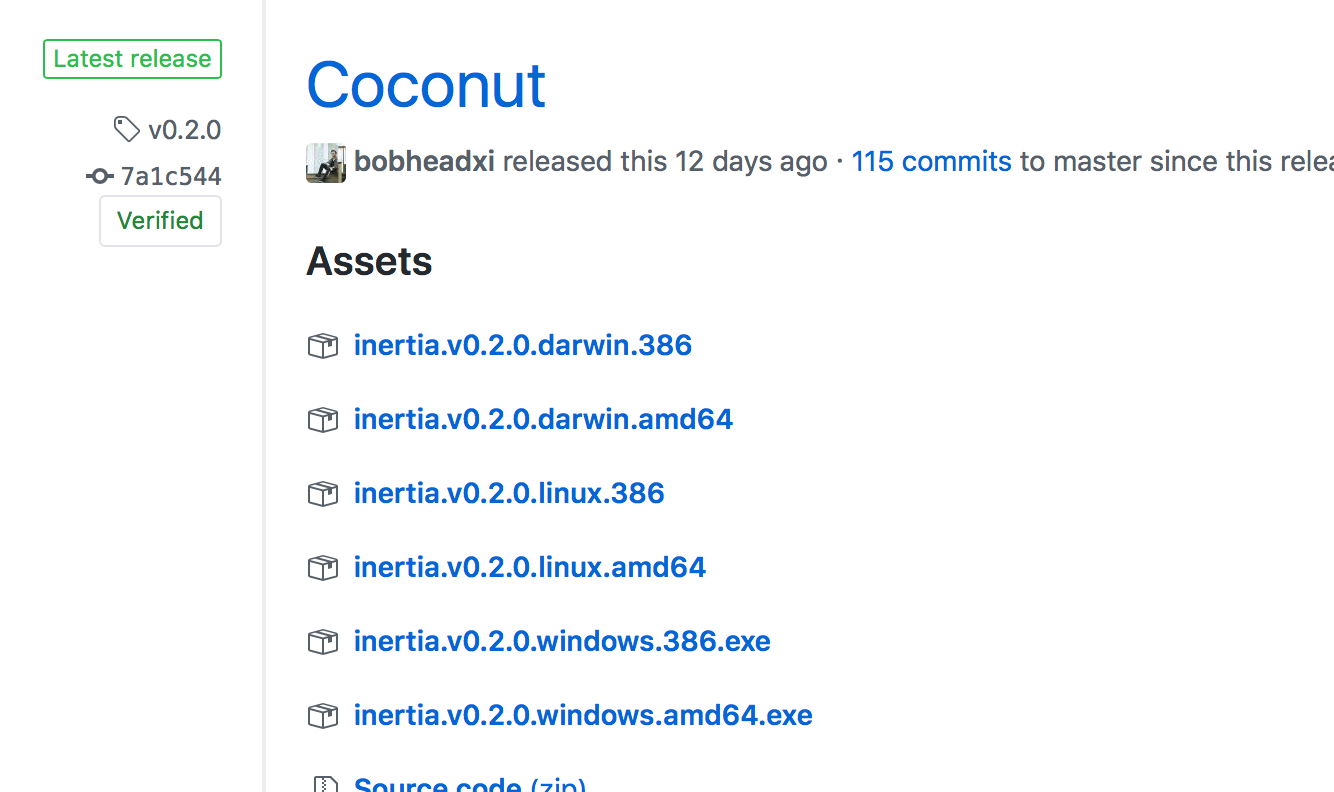

On the client-side, using Golang to build the CLI meant that we could easily cross-compile and upload executables for different platforms straight from Travis.

Kevin Yap also kindly set up a Homebrew tap for us so that Inertia can be installed by running brew install ubclaunchpad/tap/inertia🔥

# 🏗 Building and Deploying Projects

Most importantly, having Docker means that as long as projects include a Dockerfile or docker-compose configuration, Inertia should be able to build and run them without installing any additional programs. Minimising Inertia’s dependencies means introducing fewer points of potential incompatibility on different servers, which means fewer headaches during setup.

However, since the daemon itself is a Docker container (which is isolated from the host by design), we can’t actually start up containers on the server by default — we need to use Docker-socket mounting to allow us to do that. You can read more about how that works here. This does require our daemon to have sudo permissions, which has some security ramifications, but we decided it was the easiest way to pull off this functionality anyway. We are actively looking for a sudo-less way to do this though.

The actual implementation of Dockerfile and docker-compose building was not as straight-forward as I had expected. To avoid installing more stuff Inertia uses Docker’s native Golang client, but the API exposed through it is pretty barebones. For example, there is no direct equivalent for even the commonly used docker build command — we have to manually compress the source code of a project and send it to the Docker daemon, which means we have no support (yet) for features like .dockerignore files. Yikes.

// dockerBuild builds project from Dockerfile and deploys it

func dockerBuild(d *Deployment, cli *docker.Client, out io.Writer) error {

// Package project files

buildCtx := bytes.NewBuffer(nil)

common.BuildTar(d.directory, buildCtx)

dockerFilePath := "Dockerfile"

// Send project to daemon and build image

ctx := context.Background()

imageName := "inertia-build/" + d.project

buildResp, _ := cli.ImageBuild(ctx, buildCtx, types.ImageBuildOptions{

Tags: []string{imageName},

Dockerfile: dockerFilePath,

})

// Output build progress

stop := make(chan struct{})

common.FlushRoutine(out, buildResp.Body, stop)

close(stop)

buildResp.Body.Close()

// Create container from image

containerResp, _ := cli.ContainerCreate(

ctx, &container.Config{Image: imageName}, nil, nil, d.project,

)

// Start container

return cli.ContainerStart(ctx, containerResp.ID, types.ContainerStartOptions{})

}

The same goes for docker-compose — the Golang client offers no such functionality. Instead, we found a way to use the available docker/compose Docker image to do more or less the same thing. Programmatically, this is pretty similar to the Docker build — you can read more about it here. Interestingly enough, this means that we use a Docker container (the daemon) to start a container (docker/compose) to start more containers (the user’s project). 😧

With this functionality, users just have to provide some minimal Docker configuration with their projects for Inertia to work. Setting a project up for Docker is flexible, well-documented, and pretty easy to do.

However, we wanted to go a little further. I’ve always found Heroku’s support for different languages pretty impressive: it typically requires nothing more than a one-line Procfile and, given Heroku’s popularity, I figured it might be cool if Inertia could deploy Heroku-configured projects, or at least pull off something similar.

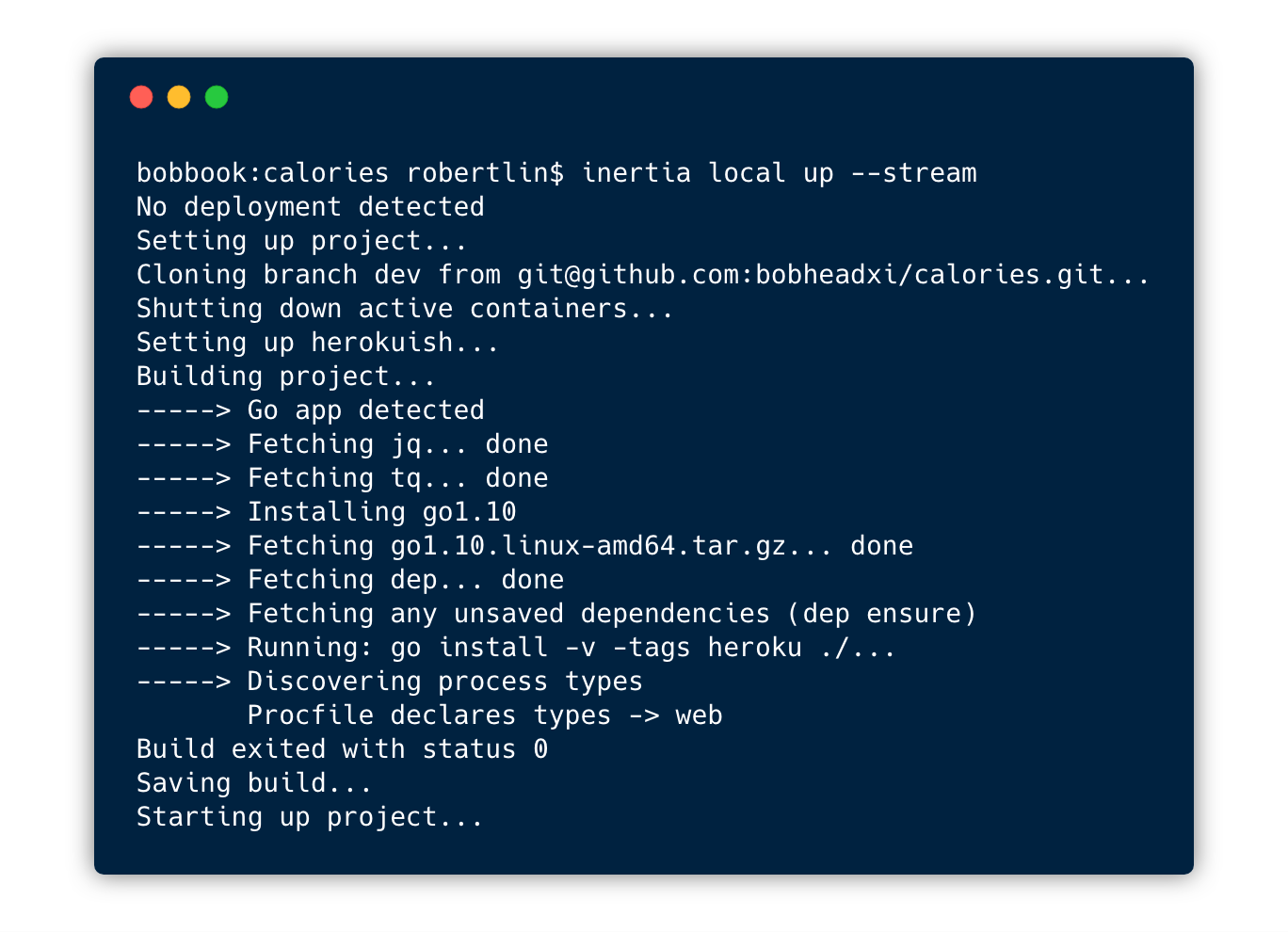

It turns out that the scripts that Heroku uses to build projects — called “buildpacks” — are actually open source and free to use! These buildpacks turn projects into executable “slugs”, and a pretty wide variety are available, covering everything from Java and Scala to Node and Python applications. Even more awesome is that a tool that emulates Heroku’s entire build and run process using these buildpacks exists in the form of the aptly named community project Herokuish. This tool conveniently comes in a Docker image, which Inertia uses similarly to the docker/compose image to provide Heroku-like builds and deployments using Docker.

An example from my pull request introducing this feature.

Heroku still offers a ton of extra features, however, such as multiple procs, plugins, rolling deployments… but for the time being, this is pretty handy to have, especially with Heroku’s limited free server uptime and its rather slow start up times if you don’t pay.

# 🤺 User Interfaces

All this work would be pretty pointless if the user-facing components are too hard to use. One important part of the user experience — and one of our initial design goals — is simple setup. Since Docker is our only dependency, Inertia setup just involves executing a script over SSH that installs Docker, pulls and runs an ubclaunchpad/inertia image from DockerHub, and sets up an additional RSA key and JSON Web Token for authentication.

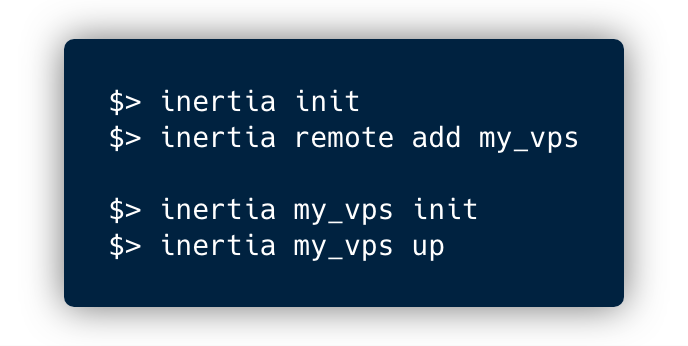

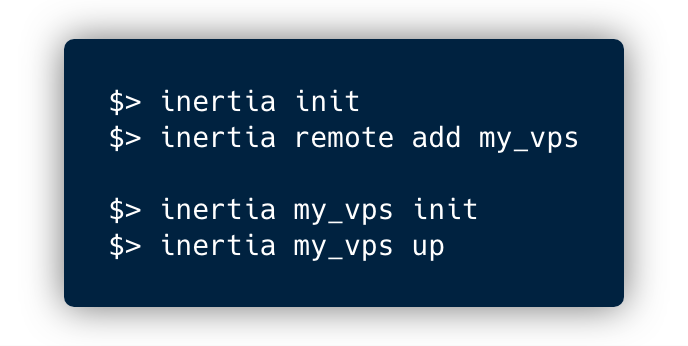

First two steps set up local configuration, and the last two set up the remote.

All this can be done with minimal fuss in just four steps, without ever leaving the user’s local shell. 😎

Well, you do have to head over to your GitHub repository to register a public key (so that Inertia can clone your project) and the daemon’s WebHook address (so the daemon can be notified of updates) — this hasn’t proven overly cumbersome yet, though we are considering OAuth support.

Recently we’ve added a web app to Inertia as well, packaged into the daemon’s image through a multi-staged Docker build. The CLI offers commands that allows you to add your teammates as users, after which they can log in to the web app through the daemon’s port and view the deployed application’s logs from anywhere. We’re hoping to add more features to this web app soon to allow teams more flexibility.

# 🔑 Security

Security is pretty important for a tool like Inertia, where unauthorised access could wreak havoc on deployments. To make sure access is restricted, all communications require some sort of authentication — the CLI uses signed tokens, and a session management module tracks web interface authentication through cookies. To secure all these communications, Inertia uses HTTPS across the board through a self-signed SSL certificate. Standard measures like password encryption are also used.

# 🛠 Making Sure Everything Works

As an application that relies heavily on other things — scripts, Docker, user projects, the deployment environment, and so on — unit tests don’t really cut it. We need to make sure that:

- our Docker install and bootstrapping over SSH works

- the daemon starts up correctly and is accessible

- projects of different types build and deploy correctly

- Git functionality (built on the pure Go implementation, go-git) works as expected, such as project updating and branch switching

We also needed to be able to do manual testing as we worked without constantly needing a real remote host to use, while making sure all server-side functionality worked consistently across different platforms.

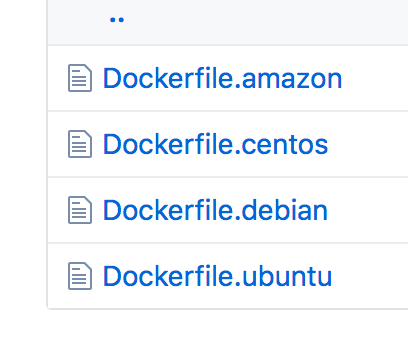

🐋 Dockerfiles galore!

To do this, I set up a set of Dockerfiles that can emulate real servers of different platforms, complete with SSH access using a pre-generated RSA key saved in our repository.

Once started, these simulated servers can be used to locally start up an Inertia daemon and deploy a project.

The previously mentioned RSA key is registered to a test repository in order to make sure Git functionality works. There are also some test projects to test the build processes of each of our three supported project types.

Travis is set up to run all of our unit and integration tests on each of the mock remotes, effectively making sure our stuff consistently works across a range of platforms.

# 🚀 The Road Forward

Inertia has come a long way since we first started work on it — it is already being used to continuously deploy several of UBC Launch Pad’s projects, such as the online game Bumper. Recently, Chad Lagore and I made a brief presentation about the project at Vancouver DevOpsDays conference.

There is still much room for improvement, however, and the project remains under active development. We have a ton of ideas and features we want to implement going forward, and hope that this will not just be a useful tool but also a great entrypoint for anyone who wants to explore the world of Docker and deployment applications.

Check out the Inertia repository if you are interested in using Inertia or want to learn more and contribute! Any sort of feedback — ideas, bug reports, anything — would also be greatly appreciated. Keep an eye on our repository for future releases and new features! ✨