Extending Sourcegraph search

hacking in search notebooks search for Sourcegraph

- 34 minsSourcegraph recently held a brief internal hackathon where we got to work on a variety of ideas related to our freshly minted “Sourcegraph use cases”. One idea that was raised was extending Sourcegraph’s core code search functionality to allow queries over search notebooks, a new product that enables live and persistent documentation based on code search, to aid in content discovery for onboarding.

The minimum viable product of this project was to implement the ability to do the following search within the Sourcegraph search language:

type:notebook my notebook query select:notebook.block.md

_____________ _________________ ________________________

| | └ render Markdown sections of the notebook match

| └ query string

└ type filter

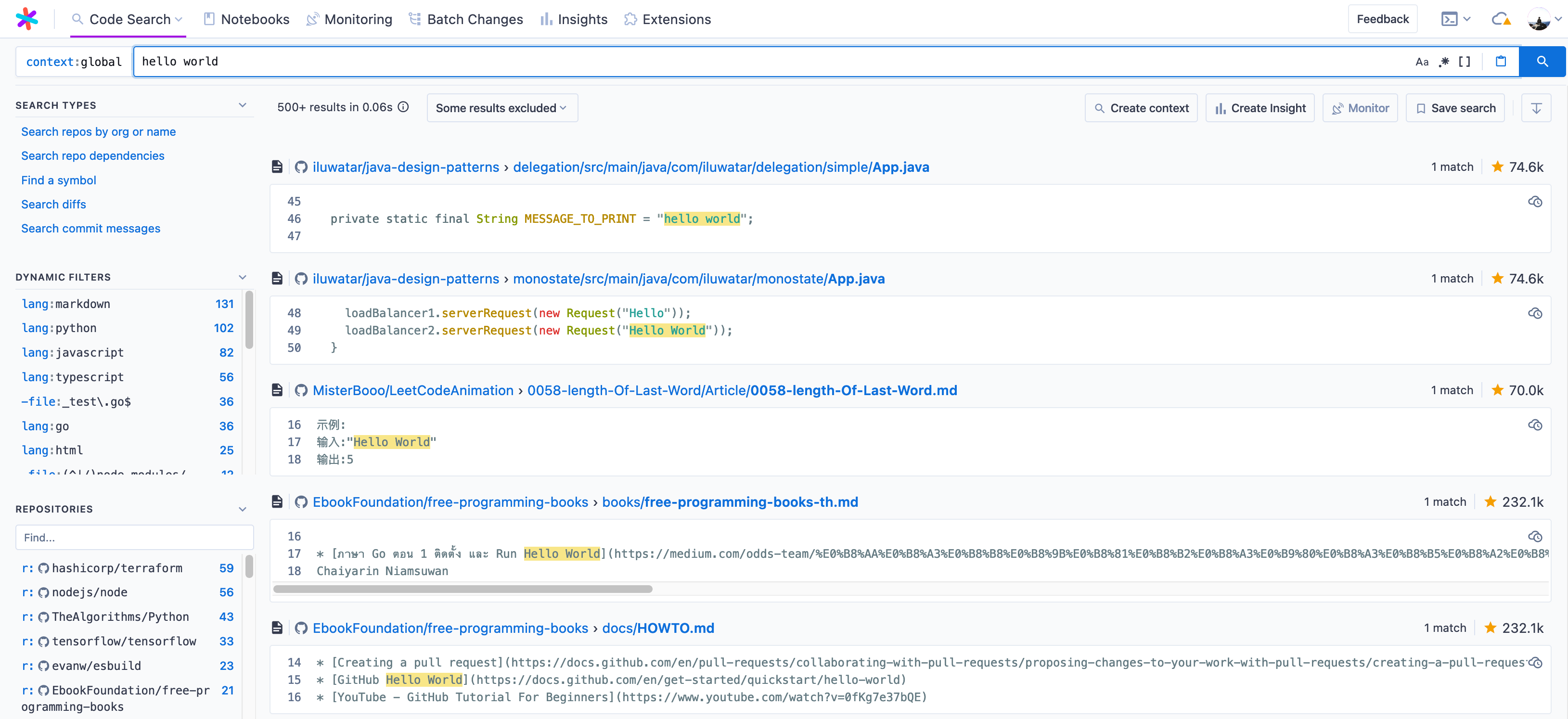

And render search notebooks (and/or selected “blocks”, or sections) within search results! For some context, this is what Sourcegraph’s code search results usually look like:

And this is what search notebooks look like, with each section being a separate notebook block:

In this post, I’ll walk through a brief overview of what I learned about how Sourcegraph search works and what we did to implement an additional search and search result type!

- Introducing a search job

- Sending results over the wire

- Querying the database for real results

- Implementing notebook blocks results

- Rendering search notebook results

A sneak peak of the end result:

Note that all the code internals mentioned in this post may change - you can view the Sourcegraph repository at 73a484e for a accurate picture of what the codebase looked like at the time! I’d also like to thank @tsenart who both proposed the original idea and worked with me through several brainstorming sessions to discuss the implementation.

Additionally, I am basically a complete outsider when it comes to our search internals, and the search code I interact with in this post was built by Sourcegraph’s fantastic search teams, so kudos1 to the teams for making this hack possible in the first place!

# Introducing a search job

When you enter a query into sourcegraph.com/search:

- A client makes a request to (typically) the

/.api/streamendpoint - see how it is done in theraycast-sourcegraphextension for a simplified example. - The query makes its way to

sourcegraph-frontend, which converts the query text into a search plan composed of search jobs to execute against various backends (such as Zoekt). - Jobs get executed and the results get streamed back over the wire to the client.

For example, a typical query foobar will evaluate to a plan of jobs like the following, calling out to a variety of search backends (ZoektGlobalSearch, RepoSearch, ComputeExcludedRepos) within certain limits2, imposed by jobs for enforcing those limits on child jobs.

flowchart TB

0([TIMEOUT])

0---1

1[20s]

0---2

2([LIMIT])

2---3

3[500]

2---4

4([PARALLEL])

4---5

5([ZoektGlobalSearch])

4---6

6([RepoSearch])

4---7

7([ComputeExcludedRepos])

The typical example here is a search job that reaches out to our Zoekt backends. A Job could also combine multiple search jobs, such as to run a set of jobs in parallel or to prioritise results from certain jobs before others.

The evaluated search job varies based on your search query - an exhaustive commit search (foo type:commit count:all) will create the following job instead, with a longer timeout and higher limit:

flowchart TB

0([TIMEOUT])

0---1

1[1m0s]

0---2

2([LIMIT])

2---3

3[99999999]

2---4

4([PARALLEL])

4---5

5([Commit])

4---6

6([ComputeExcludedRepos])

Each search job within these plans are implemented behind the Job interface:

// Job is an interface shared by all individual search operations in the

// backend (e.g., text vs commit vs symbol search are represented as different

// jobs) as well as combinations over those searches (run a set in parallel,

// timeout). Calling Run on a job object runs a search.

type Job interface {

Run(context.Context, database.DB, streaming.Sender) (*search.Alert, error)

Name() string

}

So how do these jobs in the query plan get created? Poking around for constructors of the Job interface reveals (I think) the following flow for Job creation after a query.Plan is created (primarily with query.Pipeline, which handles query parsing, validation, transformation, and so on):

graph TD

FromExpandedPlan --> ToEvaluateJob

ToEvaluateJob --> ToSearchJob

ToEvaluateJob -- "has pattern (AND or OR)" --> toPatternExpressionJob

toPatternExpressionJob --> ToSearchJob

toPatternExpressionJob --> toOrJob

toPatternExpressionJob --> toAndJob

toOrJob --> toPatternExpressionJob

toAndJob --> toPatternExpressionJob

ToSearchJob --> Job

ToSearchJob -- has pattern --> optimizeJobs

optimizeJobs --> Job

The ToSearchJob function, which appears to handle the bulk of creation of search jobs, with the additional layers applying a variety of processing.

// ToSearchJob converts a query parse tree to the _internal_ representation

// needed to run a search routine. To understand why this conversion matters, think

// about the fact that the query parse tree doesn't know anything about our

// backends or architecture. It doesn't decide certain defaults, like whether we

// should return multiple result types (pattern matches content, or a file name,

// or a repo name). If we want to optimise a Sourcegraph query parse tree for a

// particular backend (e.g., skip repository resolution and just run a Zoekt

// query on all indexed repositories) then we need to convert our tree to

// Zoekt's internal inputs and representation. These concerns are all handled by

// toSearchJob.

func ToSearchJob(jargs *Args, q query.Q, db database.DB) (Job, error) {

b, err := query.ToBasicQuery(q)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

types, _ := q.StringValues(query.FieldType)

resultTypes := search.ComputeResultTypes(types, b.PatternString(), jargs.SearchInputs.PatternType)

// ...

var requiredJobs, optionalJobs []Job

addJob := func(required bool, job Job) {

if required {

requiredJobs = append(requiredJobs, job)

} else {

optionalJobs = append(optionalJobs, job)

}

}

// ... various conditional calls to addJob

}

So to start off, we add a new field type result.TypeNotebook = "notebook", and attach a new Job when a query includes type: notebook:

if resultTypes.Has(result.TypeNotebook) {

notebookSearchJob := ¬ebook.SearchJob{

PatternString: b.PatternString(),

}

addJob(true, notebookSearchJob)

}

For now, we want to create a stub implementation that provides a few hard-coded notebooks that sends a few results over to the streaming.Sender provided in the (Job).Run interface. This requires implementing the result.Match interface:

type Match interface {

ResultCount() int

// Limit truncates the match such that, after limiting,

// `Match.ResultCount() == limit`. It should never be called with

// `limit <= 0`, since a single match cannot be truncated to zero results.

Limit(int) int

Select(filter.SelectPath) Match

RepoName() types.MinimalRepo

// Key returns a key which uniquely identifies this match.

Key() Key

}

Right off the bat, it becomes clear that Sourcegraph’s search internals are heavily geared towards repository-oriented results, with the top-level RepoName being part of the Match interface. Repository matches, file content results, symbols, commits, diffs, and so on all return results that are part of a repository. Notebooks, on the other hand, are an entirely separate entity within the Sourcegraph application, and notebooks that are tracked in the database (it is also possible to create notebooks with .snb.md files within repositories, but we ignore that case for now) are not strictly associated with any repository.

This is even more evident within the Key type, which requires an unique combination Repo, Rev, Path, AuthorDate, Commit, Path, and TypeRank - none of which are fields that we can use to uniquely identify a search notebook. We could use Path as the notebook name, but that’s not strictly unique either.

To work around these issues for now, we just return a zero-value RepoName and add a new field ID to the Key type:

type Key struct {

// ...

// ID is an arbitrary identifier that can be used to distinguish this result,

// e.g. if the result type is not associated with a repository.

ID string

// ...

}

type NotebookMatch struct {

ID int64

Title string

Namespace string

Private bool

Stars int

}

func (n NotebookMatch) RepoName() types.MinimalRepo {

// This result type is not associated with any repository.

return types.MinimalRepo{}

}

func (n NotebookMatch) Limit(limit int) int {

// Always represents one result and limit > 0 so we just return limit - 1.

return limit - 1

}

func (n *NotebookMatch) URL() *url.URL {

return &url.URL{Path: "/notebooks/" + n.marshalNotebookID()}

}

func (n *NotebookMatch) Key() Key {

return Key{

ID: n.marshalNotebookID(),

TypeRank: rankRepoMatch,

}

}

// other interface functions no-op for now

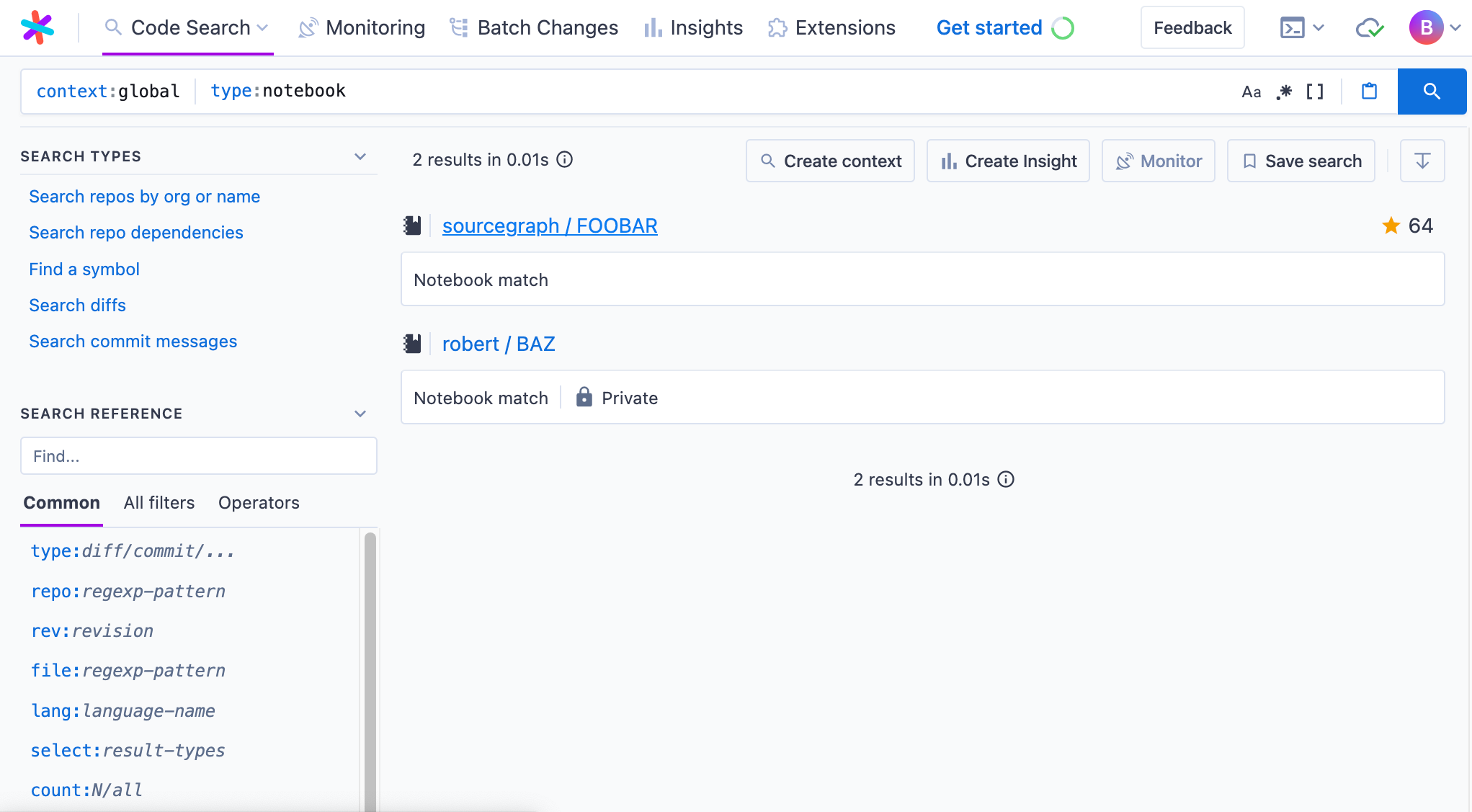

With our new types, we can create a stub job for searching search notebooks:

type SearchJob struct {}

func (s *SearchJob) Run(ctx context.Context, db database.DB, stream streaming.Sender) (*search.Alert, error) {

stream.Send(streaming.SearchEvent{

Results: result.Matches{

&result.NotebookMatch{

Title: "FOOBAR",

Namespace: "sourcegraph",

ID: 1,

Stars: 64,

Private: false,

},

&result.NotebookMatch{

Title: "BAZ",

Namespace: "robert",

ID: 2,

Stars: 0,

Private: true,

},

},

})

return nil, nil

}

func (*SearchJob) Name() string { return "NotebookSearch" }

The workarounds above caused some funky behaviour, such as repository permissions post-processing rejecting notebook results as not being associated with a repository the current actor (user) has access to, so I just hacked in some a condition to ignore zero-value RepoNames in those checks to avoid dropping our notebook results.

We can test the evaluation of the query type:notebook select:notebook.block.md foobar to see our new search job type being registered (after implementing the appropriate printers):

flowchart TB

0([TIMEOUT])

0---1

1[20s]

0---2

2([LIMIT])

2---3

3[500]

2---4

4([SELECT])

4---5

5[notebook.block.md]

4---6

6([PARALLEL])

6---7

7([NotebookSearch])

6---8

8([ComputeExcludedRepos])

In this case, the select: term is just thrown in to demonstrate that it’s a job that occurs on top of a child job, which contains the NotebookSearch job we created. This will be important later)!

# Sending results over the wire

That’s not the end of it! Distinct from plans, jobs, and matches, we also have event types, which are the types that get transmitted over the wire to search clients.

For the most part, this is a very thin layer that just simplifies the internal match types for consumption, and hydrates events with repository metadata from a cache (such how many stars the associated repository has, and when the repository was last updated) or decorations. For our new notebook results, we don’t really need to support any of that yet - we can simply map results more or less directly to a new event type.

func fromNotebook(notebook *result.NotebookMatch) *streamhttp.EventNotebookMatch {

return &streamhttp.EventNotebookMatch{

Type: streamhttp.NotebookMatchType,

ID: notebook.Key().ID,

Title: notebook.Title,

Namespace: notebook.Namespace,

URL: notebook.URL().String(),

Stars: notebook.Stars,

Private: notebook.Private,

}

}

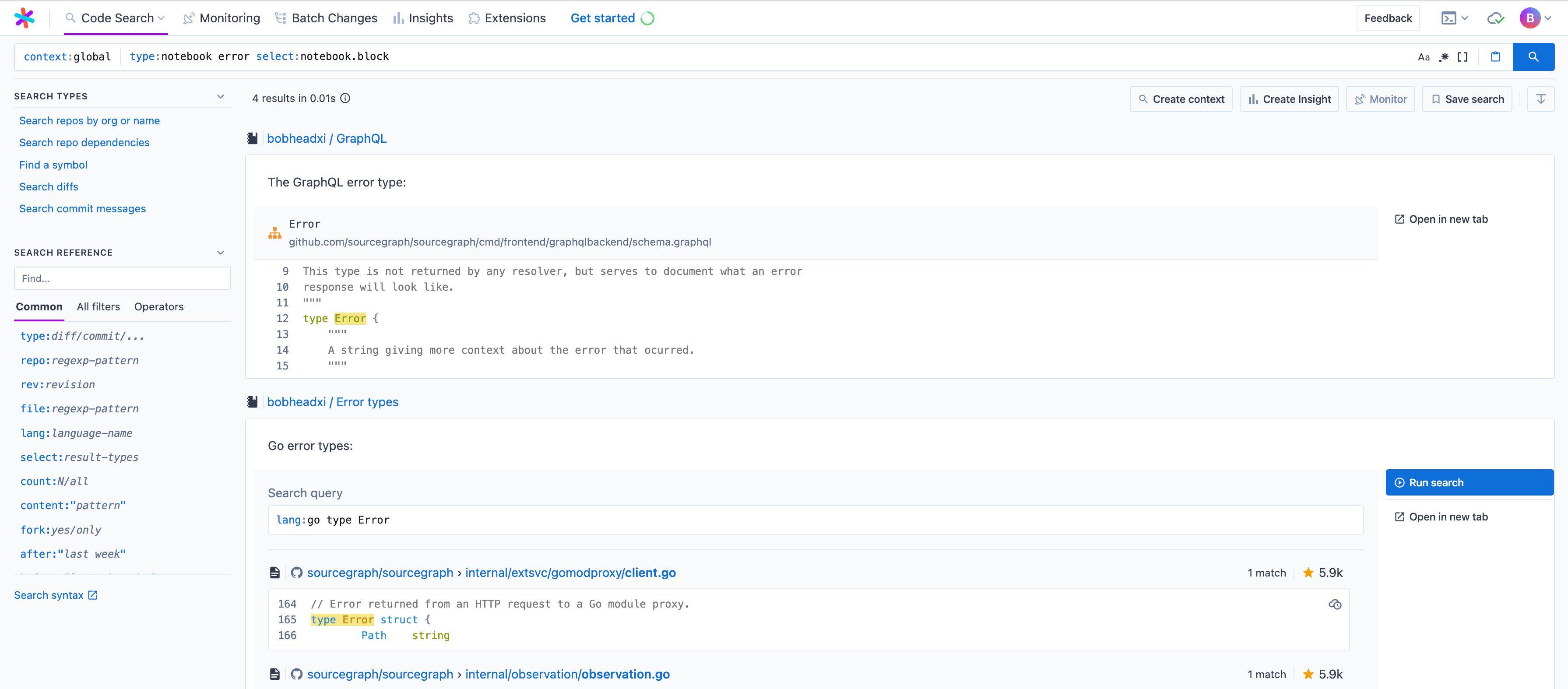

At this point, we basically have everything we need to see our results in the API results! We can confirm by spinning up Sourcegraph locally with sg start, executing a search, and inspecting the response of the network request to /.api/stream within a browser for our placeholder notebook results:

matches' entry for our hard-coded notebooks! # Querying the database for real results

Notebooks live in the Sourcegraph database, so to replace our stub results we can make a query to look for notebooks that returns relevant matches based on the provided query string.

SELECT

notebooks.id,

notebooks.title,

NOT public as private, -- invert for consistency with other match types

-- apply post-processing after query to merge namespace_user and namespace_org into a

-- single 'Namespace' field (only one can be set at a time)

users.username as namespace_user,

orgs.name as namespace_org,

(

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM notebook_stars

WHERE notebook_id = notebooks.id

) as stars

FROM

notebooks

LEFT JOIN users on users.id = notebooks.namespace_user_id

LEFT JOIN orgs on orgs.id = notebooks.namespace_org_id

WHERE

(%s) -- permission conditions

AND (%s) -- query conditions

ORDER BY

stars DESC

LIMIT

25

To generate query conditions, we use the notebook.SearchJob evaluated in ToSearchJob as the sole parameter. The idea is to extend SearchJob to contain all the parameters that can be used to adjust the generated query (such as pattern types, e.g. regexp, or additional fields, such as inclusion and exclusion of notebooks with notebook: and -notebook, and so on). For now, we generate simple queries solely based on the PatternString parameter:

func makeQueryConds(job *SearchJob) *sqlf.Query {

conds := []*sqlf.Query{}

// Allow querying against the 'full title'

const concatTitleQuery = "CONCAT(users.username, orgs.name, notebooks.title)"

if job.PatternString != "" {

titleQuery := "%(" + job.PatternString + ")%"

conds = append(conds, sqlf.Sprintf("%s ILIKE %s",

concatTitleQuery, titleQuery))

}

if len(job.PatternString) > 0 {

// Query against notebook contents, embedded as a tsvector field.

conds = append(conds, sqlf.Sprintf("notebooks.blocks_tsvector @@ to_tsquery('english', %s)",

toPostgresTextSearchQuery(job.PatternString)))

}

if len(conds) == 0 {

// If no conditions are present, append a catch-all condition to avoid a SQL syntax error

conds = append(conds, sqlf.Sprintf("1 = 1"))

}

return sqlf.Join(conds, "\n OR")

}

The CONCAT means that we cannot use indexes to hasten the query, but this is a hackathon so oh well. I decided to keep it in because I felt like a query for $namespace $topic felt like a very natural query to want to make, and I wanted to the demo supported that.

After writing a bit more boilerplate to execute the database query and scan the resulting rows, we can update our search job to return real results instead:

func (s *SearchJob) Run(ctx context.Context, db database.DB, stream streaming.Sender) (*search.Alert, error) {

store := Search(db)

notebooks, err := store.SearchNotebooks(ctx, s)

if err != nil {

return nil, errors.Wrap(err, "NotebookSearch")

}

matches := make([]result.Match, len(notebooks))

for i, n := range notebooks {

matches[i] = n

}

stream.Send(streaming.SearchEvent{

Results: matches,

})

return nil, nil

}

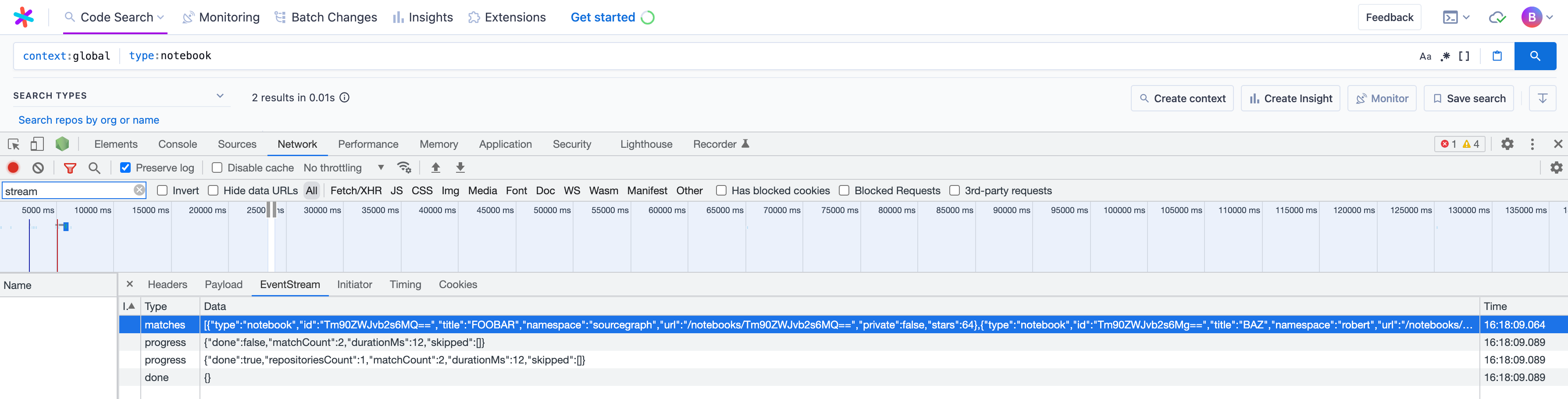

We can test this out by creating a few notebooks in our local Sourcegraph instance and inspecting the network requests in-browser again to see real notebooks being returned!

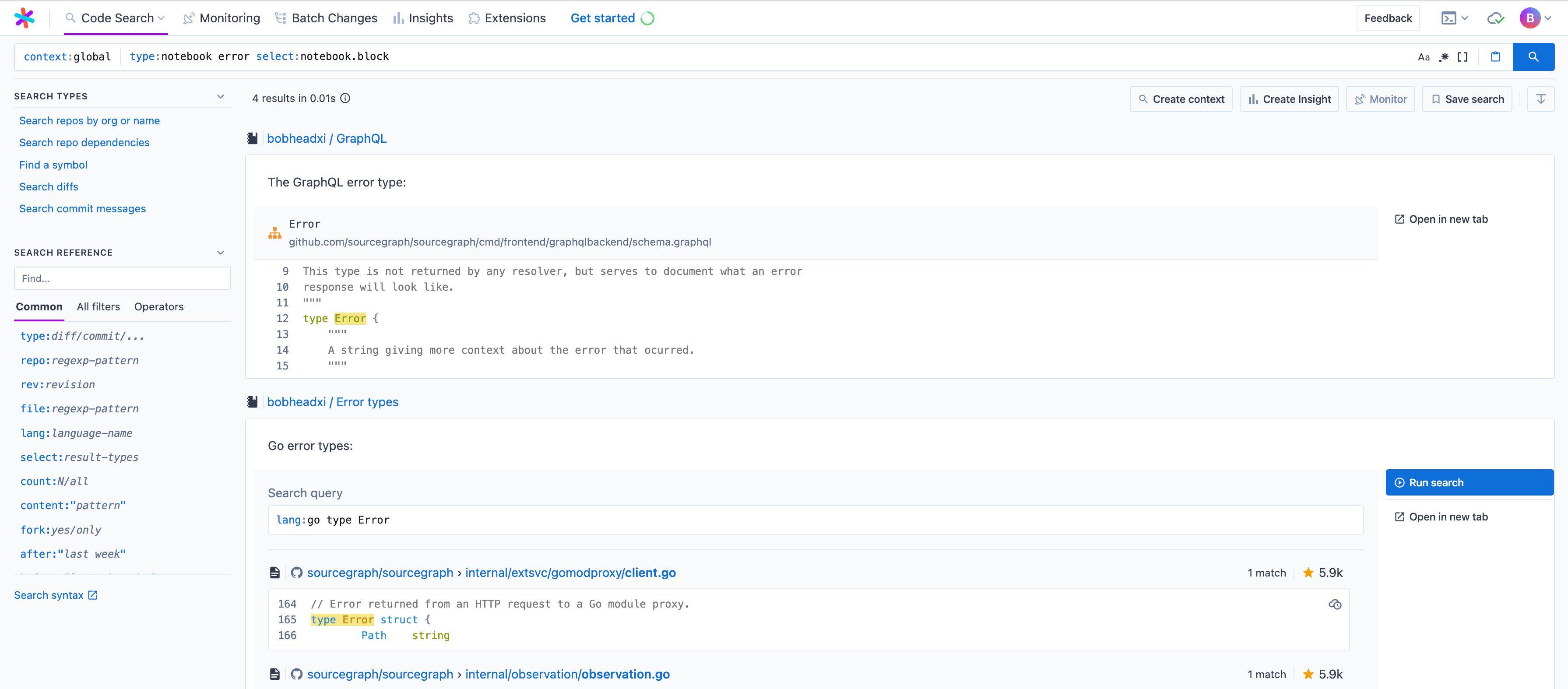

# Implementing notebook blocks results

Seeing the notebook titles that match your query is great and all, but to demonstrate the potential of this capability we wanted to make sure users can also see notebook content results - in other words, the matching notebook blocks - for their query.

For now, we decided to implement this such that notebook blocks only get returned with the select:notebook.block parameter. The Sourcegraph query language already features selections like select:repo or select:commit.diff.added, so this approach felt like it fitted in with how other search types are implemented.

Selections are part of the Match interface we previously implemented, and they work via selectJob, which wraps the streaming.Sender with another streaming.Sender that calls Select on each result it receives before passing it to the underlying stream.

This means that all we have to do is also query for blocks within our notebooks database query, and only expose the blocks within the Select implementation. To start off, we extend our NotebookMatch with a Blocks field, and implement Select such that we generate a new NotebookBlocksMatch type:

type NotebookMatch struct {

// ... as before

Blocks NotebookBlocks `json:"-"`

}

/// ... as before

func (n *NotebookMatch) Select(path filter.SelectPath) Match {

// Only support 'select:notebook.*' on this result type

if path.Root() != filter.Notebook {

return nil

}

switch len(path) {

case 1:

return n // This is just 'select:notebook', so return self

case 2, 3: // Support 'select:notebook.block' and 'select:notebook.block.*'

if path[1] == "block" {

if len(n.Blocks) == 0 {

return nil // No results!

}

return (&NotebookBlocksMatch{

Notebook: *n,

Blocks: n.Blocks,

}).Select(path) // Allow blocks to continue selecting for 'select:notebook.block.*'

}

}

return nil

}

To support select:notebook.blocks.$TYPE, where $TYPE is a block type (such as Markdown, query, symbol, and so on), the NotebookBlocksMatch type must also implement Select to only provide blocks of the requested type:

func (n *NotebookBlocksMatch) Select(path filter.SelectPath) Match {

// Only support 'select:notebook.*' on this result type

if path.Root() != filter.Notebook {

return nil

}

switch len(path) {

case 2:

if path[1] == "block" {

return n // This is just 'select:notebook.block', so return self

}

case 3:

// Filter by the requested block type, which is the third path parameter. For example,

// 'select:notebook.block.md' will filter for blocks of type 'md'.

blockType := path[2]

var blocks NotebookBlocks

for _, b := range n.Blocks {

if b["type"] == blockType {

blocks = append(blocks, b)

}

}

if len(blocks) == 0 {

return nil // No results!

}

return &NotebookBlocksMatch{

Notebook: n.Notebook,

Blocks: blocks,

}

}

return nil

}

And as before, we need to implement an event type EventNotebookBlockMatch and the relevant adapters as well.

func fromNotebookBlocks(blocks *result.NotebookBlocksMatch) *streamhttp.EventNotebookBlockMatch {

return &streamhttp.EventNotebookBlockMatch{

Type: streamhttp.NotebookBlockMatchType,

Notebook: *fromNotebook(&blocks.Notebook),

Blocks: blocks.Blocks,

}

}

For the database layer, we now need to add blocks to our result type. Blocks are currently store as a JSON blob within the notebooks.blocks column, so adding that to our SELECT and including it in the result scan is fairly straight-forward.

However, this does mean that we can’t only select relevant blocks within the database query. A better long-term solution to this is likely to split notebooks.blocks out into a separate table and joining it at query time, but that’s a lot of work for a hackathon so I decided to go for a cheap hack: post-filtering! This isn’t too bad for now because the notebooks.blocks_tsvector @@ to_tsquery in our query conditions means that the returned notebooks are likely to have a matching block, but it definitely isn’t very pretty.

Even worse, blocks of various types have varying shapes (i.e. there’s no single block.text field we can filter on), and I didn’t want to special-case each block type for now. A closer look at notebooks.blocks_tsvector reveals it is backed by a magic Postgres feature that indexes all fields of type string within the notebooks.blocks JSON:

ALTER TABLE

notebooks

ADD

COLUMN

IF NOT EXISTS

blocks_tsvector TSVECTOR

GENERATED ALWAYS AS

(jsonb_to_tsvector('english', blocks, '["string"]')) STORED;

It is a neat implementation that does not require any knowledge of blocks fields, but sadly there does not seem to be an equivalent function built with Go for us to post-filter with. So I just marshal each block as JSON and do a regexp search over the whole thing:

func (s *notebooksSearchStore) SearchNotebooks(ctx context.Context, job *SearchJob) ([]*result.NotebookMatch, error) {

// ... query for notebooks

// do our post-filtering

if len(job.PatternString) > 0 {

searchRe, err := regexp.Compile("(?i).*(" + job.PatternString + ").*")

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

for _, n := range notebooks {

var matchBlocks result.NotebookBlocks

// filter notebook blocks

for _, block := range n.Blocks {

b, err := json.Marshal(block)

if err != nil {

continue

}

// regexp match over the marshalled block

if searchRe.Match(b) {

matchBlocks = append(matchBlocks, block)

}

}

n.Blocks = matchBlocks

}

}

return notebooks, nil

}

Hey, it’s a hackathon!

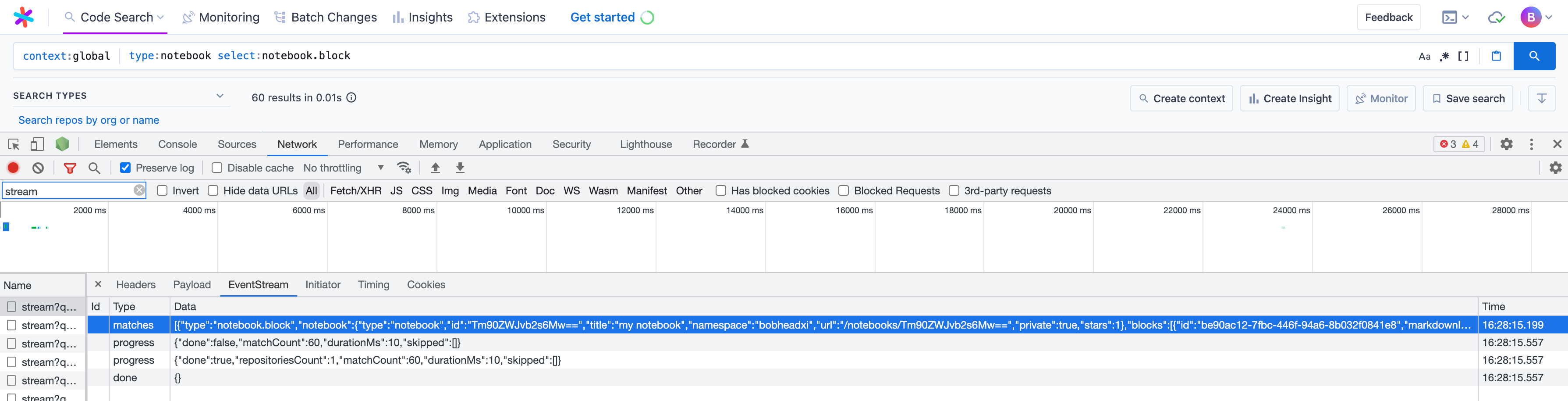

Similarly to before, we can verify this works end-to-end by running a type:notebook select:notebook.block query and inspecting the response:

# Rendering search notebook results

Rendering results in the network tab is great and all, but we want to demo something pretty as well! We start off by adding types in the web app that correspond to our new event types:

export type SearchType = /* ... */ | 'notebook' | null

export type SearchMatch = /* ... */ | NotebookMatch | NotebookBlocksMatch

export interface NotebookMatch {

type: 'notebook'

id: string

title: string

namespace: string

url: string

stars?: number

private: boolean

}

export interface NotebookBlocksMatch {

type: 'notebook.block'

notebook: NotebookMatch

// TODO lots of variants of these types, leave as any for now and massage the data

// as needed

blocks: any[]

}

To extend type: completions in the search bar, we update FILTERS:

export const FILTERS: Record<NegatableFilter, NegatableFilterDefinition> &

Record<Exclude<FilterType, NegatableFilter>, BaseFilterDefinition> = {

/* ... */

[FilterType.type]: {

description: 'Limit results to the specified type.',

discreteValues: () => [/* ... */, 'notebook'].map(value => ({ label: value })),

},

/* ... */

}

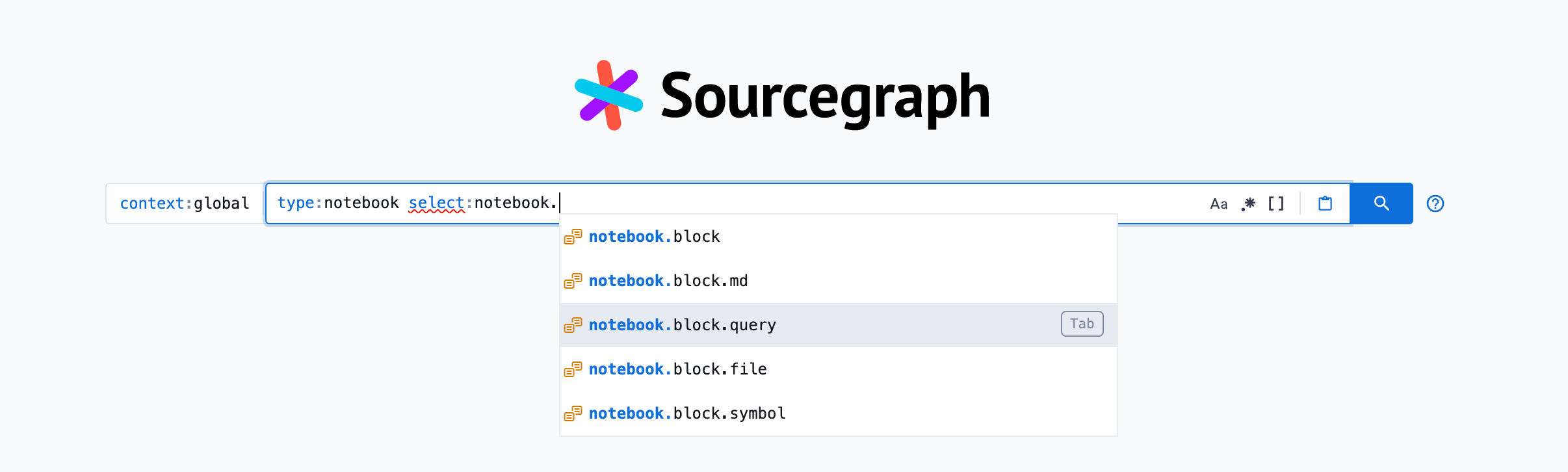

And similarly for select: completions, we update SELECTORS:

export const SELECTORS: Access[] = [

/* ... */

{

name: 'notebook',

fields: [

{

name: 'block',

fields: [{ name: 'md' }, { name: 'query' }, { name: 'file' }, { name: 'symbol' }],

},

],

},

]

And now things get a bit hacky. For plain notebook results, we can leverage the same components used for repository matches with reasonable results by extending the StreamingSearchResultsList component:

export const StreamingSearchResultsList: React.FunctionComponent<StreamingSearchResultsListProps> = ({

/* ... */

}) => {

/* ... */

const renderResult = useCallback(

(result: SearchMatch, index: number): JSX.Element => {

switch (result.type) {

/* ... */

case 'notebook':

return (

<SearchResult

icon={NotebookIcon}

result={result}

repoName={`${result.namespace} / ${result.title}`}

platformContext={platformContext}

onSelect={() => logSearchResultClicked(index, 'notebook')}

/>

)

}

}

)

return (/* ... */)

}

For notebook blocks, things started to get really hacky. I had originally expected to just render the parameters encoded in the block (for example, the query in a query block). However, @tsenart pointed out that maybe we could render the blocks exactly as it is rendered within a notebook. I thought this would be brilliant! Surely it would be as easy as simply importing the correct component and providing it with the blocks in a block match - how messy could this be?

Well, using NotebookComponent ended up looking like this:

case 'notebook.block':

return (

<ResultContainer

icon={NotebookIcon}

title={

<Link to={result.notebook.url}>

{result.notebook.namespace} / {result.notebook.title}

</Link>

}

collapsible={false}

defaultExpanded={true}

resultType={result.type}

onResultClicked={noop}

expandedChildren={

<div className={styles.notebookBlockResult}>

<NotebookComponent

key={`${result.notebook.id}-blocks`}

isEmbedded={true}

noRunButton={true}

// TODO HACK: DB, component, and GraphQL block types

// don't align so we need to massage it into a type

// this component finds acceptable

blocks={result.blocks.map(b => {

if (b.queryInput) {

return { ...b, input: { query: b.queryInput.text } }

}

return {

...b,

input:

b.markdownInput || b.fileInput || b.symbolInput || b.computeInput,

}

})}

authenticatedUser={null}

globbing={false}

isReadOnly={true}

extensionsController={extensionsController}

hoverifier={hoverifier}

platformContext={platformContext}

exportedFileName={result.notebook.title}

onSerializeBlocks={noop}

onCopyNotebook={() => NEVER}

streamSearch={() => NEVER} // TODO make this jump to new search page instead

isLightTheme={isLightTheme}

telemetryService={telemetryService}

fetchHighlightedFileLineRanges={fetchHighlightedFileLineRanges}

searchContextsEnabled={searchContextsEnabled}

settingsCascade={settingsCascade}

isSourcegraphDotCom={isSourcegraphDotCom}

showSearchContext={showSearchContext}

/>

</div>

}

/>

)

Gnarly, eh? All these fields required me to do all sorts of things to StreamingSearchResultsListProps to get the props needed. Full disclaimer: I am far from a professional when it comes to web apps and React, so I’m sure there’s a better way to do this than prop drilling, but oh well. The NotebookComponent also doesn’t feel like it was meant for this kind of import and use, given notebooks is a pretty new product and the whole philosophy of iterate fast and polish later and all.

That said, once the compiler stopped complaining the results were great - everything kind of just worked, and looked pretty good after some CSS adjustments! Even running query blocks worked nicely.

Of course, this begs the question - what if you make a notebook search, within a search notebook? Well, that works too!

You can also check out a brief final demo I made of the state of the project at the end of the hackathon for how this all ties together:

You can also check out the (messy) (and incomplete) code here: sourcegraph#33316

# Wrap-up

Thanks for reading! I hope this was an interesting glimpse at how search works at Sourcegraph. I’m not sure if this will ever make it into the product, but regardless, this was a really fun foray into a part of the codebase I’ve only interacted with at a surface level through my Sourcegraph for Raycast extension project, and learning about the abstractions used to power code search (and more!) was fascinating, and a nice change of pace from my usual work!

-

So somewhat embarrassingly, on one of my iterations of this project I complained a bit about the tedium of the many layers in the search backend, at which point I was educated by Comby (structural search) creator @rvantonder on how cleaning up the search internals is an ongoing effort and has improved significantly over the past year. One of my biggest takeaways from this project is that search a very complex system and that building a suitable abstraction for the myriad of types of search that Sourcegraph already features is a monumental undertaking! ↩

-

By default, Sourcegraph search is limited to optimise for fast results. This extensiveness of a search is configurable through the

count:andtimeout:, as well as a specialcount:allmode, as described in our documentation: Exhaustive search. ↩