Dynamic and stateless Kubernetes Jobs for stable CI

running Buildkite pipelines on dynamically dispatched agents

- 17 minsSourcegraph’s continuous integration infrastructure uses Buildkite, a platform for running pipelines on CI agents we operate. After using the default approach of scaling persistent agent deployments for a long time, we’ve recently switched over to completely stateless agents on dynamically dispatched Kubernetes Jobs to improve the stability of our CI pipelines.

In Buildkite, events (such as a push to a repository) trigger “builds” on a “pipeline” that consist of multiple “jobs”, each of which correspond to a “pipeline step”. This is all of which is managed by the hosted Buildkite service, which then dispatches Buildkite jobs onto any Buildkite agents that are live on our infrastructure that meet each job’s “queue” requirements.

Previously, our Buildkite agent fleet was operated as a simple Kubernetes Deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: buildkite-agent

# ...

spec:

replicas: 5

# ...

template:

metadata:

# ...

spec:

containers:

- name: buildkite-agent

# ...

A separate deployment, running a custom service called buildkite-autoscaler, would poll the Buildkite API for a list of running and schedule jobs and scale the fleet accordingly by making a Kubernetes API call to update the spec.replicas value in the base Deployment:

sequenceDiagram

participant ba as buildkite-autoscaler

participant k8s as Kubernetes

participant bk as Buildkite

loop

ba->>bk: list running, pending jobs

activate bk

bk-->>ba: job queue counts

deactivate bk

activate ba

ba->>ba: determine desired agent count

ba->>k8s: get Deployment

deactivate ba

activate k8s

k8s-->>ba: active Deployment

ba->>k8s: list Deployment Pods

k8s-->>ba: active Pods

deactivate k8s

ba->>k8s: set spec.replicas to desired

end

As long as there are jobs in the Buildkite queue, deployed agent pods would remain online until the autoscaler deems it appropriate to scale down. As such, multiple jobs could be dispatched onto the same agent before the fleet gets scaled down.

While Buildkite has mechanisms for mitigating state issues across jobs, and most Sourcegraph pipelines have cleanup and best practices for mitigating them as well, we occasionally still run into “botched” agents. These are particularly prevalent in jobs where tools are installed globally, or Docker containers are started but not correctly cleaned up (for example, if directories are moounted), and so on. We’ve also had issues where certain pods encounter network issues, causing them to fail all the jobs they accept. We also have jobs work “by accident”, especially in some of our more obscure repositories, where jobs rely on tools being installed by other jobs, and suddenly stop working if they land on a “fresh” agent, or those tools get upgraded unexpected.

All of these issues eventually lead us to decide to build a stateless approach to running our Buildkite agents.

# Preparing for the switch

The main Sourcegraph mono-repository, sourcegraph/sourcegraph, uses generated pipelines that create pipelines on the fly for Buildkite. Thanks to this, we could easily implement a flag within the generator to redirect builds to the new agents on a gradual basis.

var FeatureFlags = featureFlags{

StatelessBuild: os.Getenv("CI_FEATURE_FLAG_STATELESS") == "true" ||

// Roll out to 50% of builds

rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano()).Int63()%100 < 50,

}

This feature flag could be used to apply queue configuration and environment variables on builds, allowing us to easily test out larger loads on the new agents and roll back changes with ease.

# Static Kubernetes Jobs

The initial approach undertaken by the team used a single persistent Kubernetes Job. Agents would start up with --disconnect-after-job, indicating that they should consume a single job from the queue and immediately disconnect.

A new autoscaler service, job-autoscaler, was set up that pretty much did the exact same thing as the old buildkite-autoscaler, but instead of adjusting spec.replicas, it updated spec.parallelism instead, setting spec.completions and spec.backoffLimit to arbitrarily large values to prevent the Job from ever completing and shutting down.

This initial approach was used to iterate on some refinements to our pipelines to accommodate stateless agents (namely improved caching of resources). Upon rolling this out on a larger scale, however, we immediately ran into issues resulting in major CI outages, after which I outlined my thoughts in sourcegraph#32843 dev/ci: stateless autoscaler: investigate revamped approach with dynamic jobs. It turns out, we probably should not be applying a stateful management approach (scaling a single Job entity up and down) to what should probably be a stateless queue processing mechanism. I decided to take point on re-implementing our approach.

# Dynamic Kubernetes Jobs

In sourcegraph#32843 I proposed an approach where we dispatch agents by creating new Kubernetes Jobs with spec.parallelism and spec.completions set to roughly number of agents needed to process all the jobs within the Buildkite jobs queue. This would mean that as soon as all the agents within a dispatched Job are “consumed” (have processed a Buildkite job and exited), Kubernetes can clean up the Job and related resources, and that would be that. If more agents are needed, we simply keep dispatching more Jobs. This is done by a new service called buildkite-job-dispatcher.

Luckily, all the setup has been done for stateless agents with the existing Buildkite Job, so the way the dispatcher works is by fetching the deployed Job, resetting a variety of fields used internally by Kubernetes:

- in

metadata: UID, resource version, and labels - in the Job spec:

selectorandtemplate.metadata.labels

Making a few changes:

- setting

parallelism=completions= number of jobs in queue + buffer- this means that we are dispatching agents to consume the queue, and exit when done

- setting

activeDeadlineSeconds,ttlSecondsAfterFinishedto reasonable values-

activeDeadlineSecondsprevents stale agents from sitting around for too long in case, for example, a build gets cancelled -

ttlSecondsAfterFinishedensures resources are freed after use

-

- adjusting the

BUILDKITE_AGENT_TAGSenvironment variable on the Buildkite agent container

And deploying the adjusted spec as a new Job!

sequenceDiagram

participant ba as buildkite-job-dispatcher

participant k8s as Kubernetes

participant bk as Buildkite

participant gh as GitHub

loop

gh->>bk: enqueue jobs

activate bk

ba->>bk: list queued jobs and total agents

bk-->>ba: queued jobs, total agents

activate ba

ba->>ba: determine required agents

alt queue needs agents

ba->>k8s: get template Job

activate k8s

k8s-->>ba: template Job

deactivate k8s

ba->>ba: modify Job template

ba->>k8s: dispatch new Job

activate k8s

k8s->>bk: register agents

bk-->>k8s: assign jobs to agents

loop while % of Pods not online or completed

par deployed agents process jobs

k8s-->>bk: report completed jobs

bk-->>gh: report pipeline status

deactivate bk

and check previous dispatch

ba->>k8s: list Pods from dispatched Job

k8s-->>ba: Pods states

end

end

end

deactivate ba

k8s->>k8s: Clean up completed Jobs

deactivate k8s

end

As noted in the diagram above, there’s also a “cooldown” mechanism where the dispatcher waits for the previous dispatch to roll out at least partially before dispatching a new Job to account for delays in our infrastructure. Without it, the dispatcher could continuously create new agents as the visible agent count appears low, leading to overprovisioning. We do this by simply listing the Pods associated with the most recently dispatched Job, which is easy enough to track within the dispatcher.

# Observability

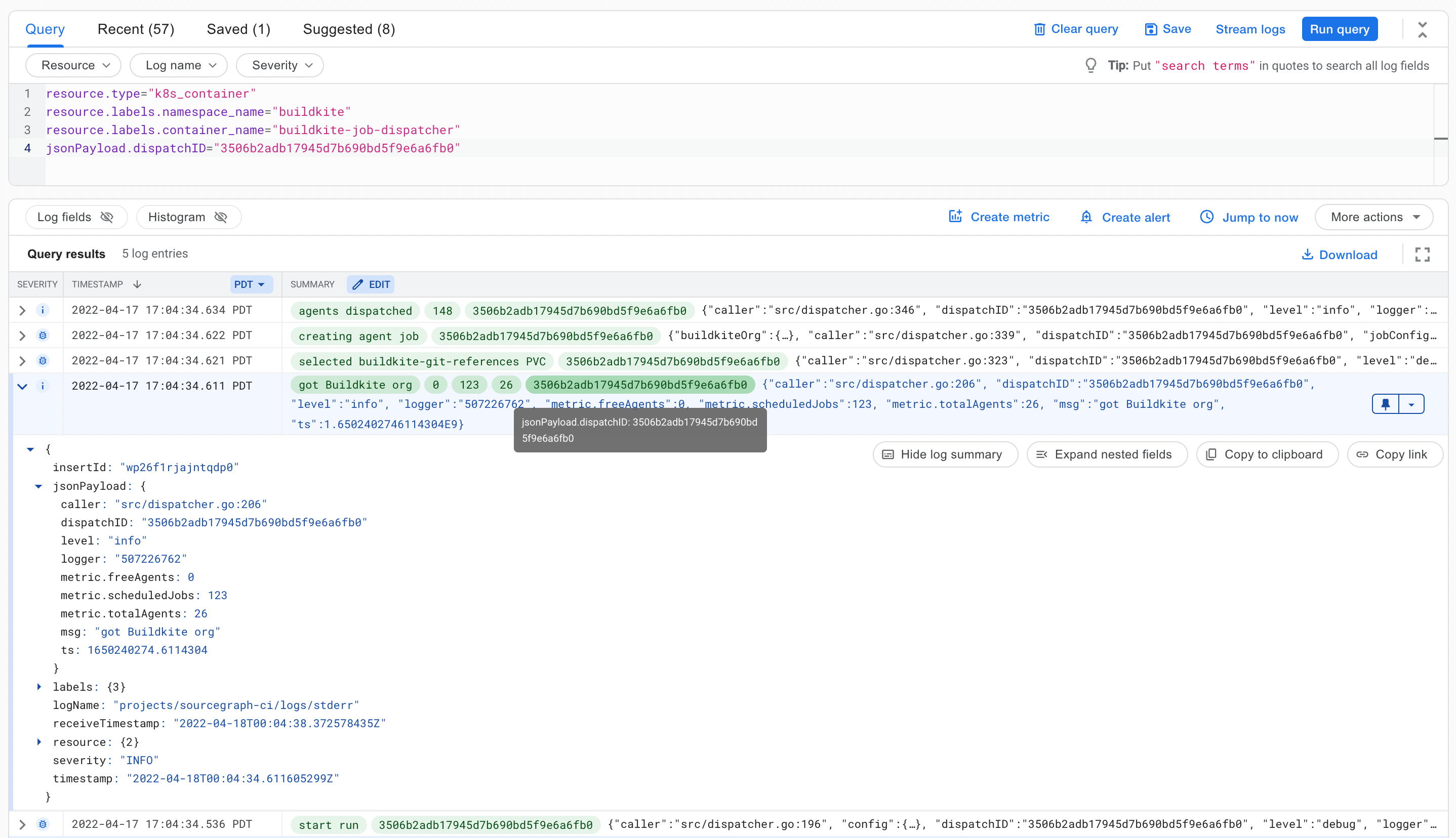

buildkite-job-dispatcher runs on a loop, with each run associated with a dispatchID, a simplified UUID with all special character removed. Everything that happens within a dispatch iteration is associated with this ID, starting with log entries, built on go.uber.org/zap:

import "go.uber.org/zap"

func (d *Dispatcher) run(ctx context.Context, k8sClient *k8s.Client, dispatchID string) error {

// Allows us to key in on a specifc dispatch run when looking at logs

runLog := d.log.With(zap.String("dispatchID", dispatchID))

runLog.Debug("start run", zap.Any("config", config))

// {"msg":"start run","dispatchID":"...","config":{...}}

}

Dispatched agents have the dispatch ID attached to their name and labels as well:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

annotations:

description: Stateless Buildkite agents for running CI builds.

kubectl.kubernetes.io/last-applied-configuration: # ...

creationTimestamp: "2022-04-18T00:04:34Z"

labels:

app: buildkite-agent-stateless

dispatch.id: 3506b2adb17945d7b690bd5f9e6a6fb0

dispatch.queues: stateless_standard_default_job

This means that when something unexpected happens - for example, when agents are underpovisioned or overprovisioned, we can easily look at the Jobs dispatched and link back to the log entries associated with their creation:

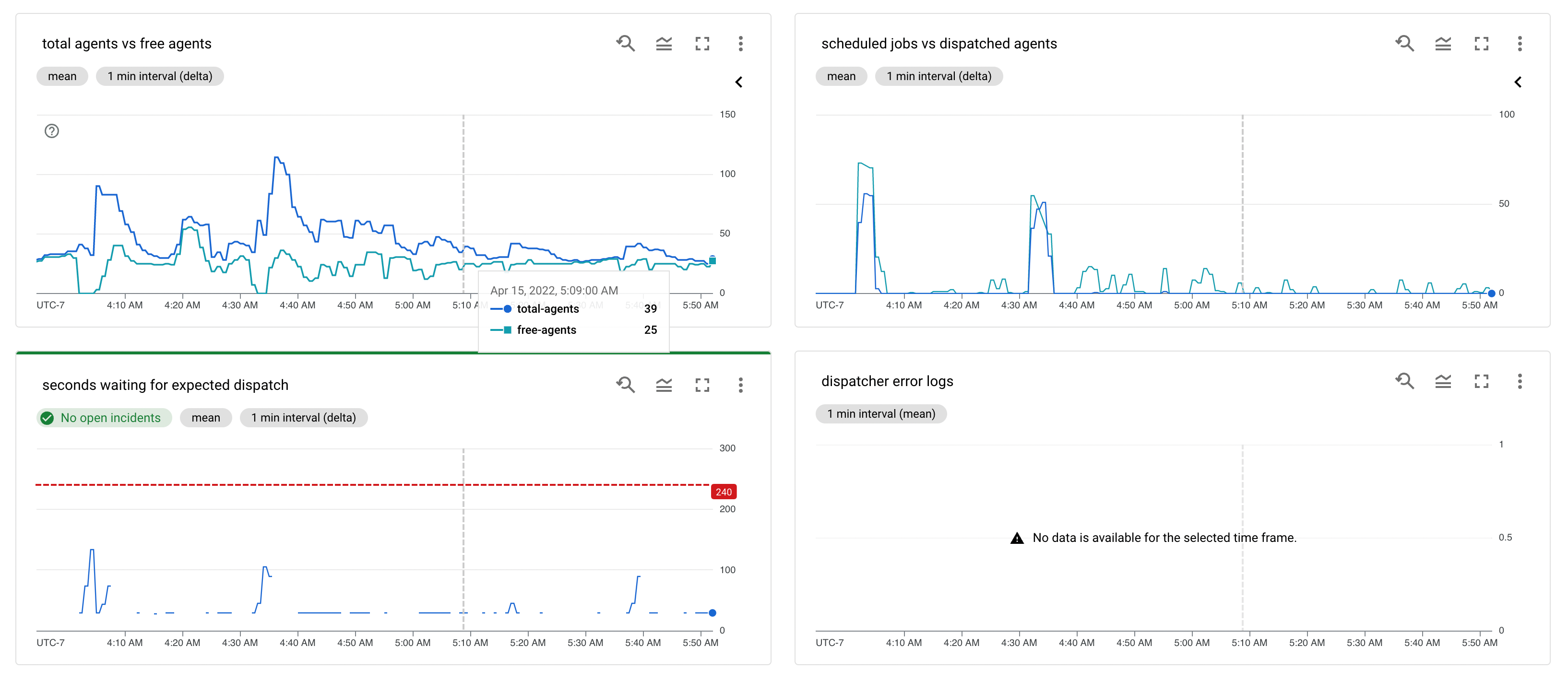

The dispatcher’s structured logs also allow us to leverage Google Cloud’s log-based metrics by generating metrics from numeric fields within log entries. These metrics form the basis for our at-a-glance overview dashboard of the state of our Buildkite agent fleet and how the dispatcher is responding to demand, as well as alerting for potential issues (for example, if Jobs are taking too long to roll out).

Based on these metrics, we can make adjustments to the numerous knobs available for fine-tuning the behaviour of the dispatcher: target minimum and maximum agents, the frequency of polling, the ratio of agents to require to come online before starting a new dispatch, agent TTLs, and more.

# Git mirror caches

During the initial stateless agent implementation, my teammates @jhchabran and @davejrt developed some nifty mechanisms for caching asdf (a tool management tool) and Yarn dependencies. It uses a Buildkite plugin for caching under the hood, and exposes a simple API for use with Sourcegraph’s generated pipelines:

func withYarnCache() buildkite.StepOpt {

return buildkite.Cache(&buildkite.CacheOptions{

ID: "node_modules",

Key: "cache-node_modules-{{ checksum 'yarn.lock' }}",

RestoreKeys: []string{"cache-node_modules-{{ checksum 'yarn.lock' }}"},

Paths: []string{"node_modules", /* ... */},

Compress: false,

})

}

func addPrettier(pipeline *bk.Pipeline) {

pipeline.AddStep(":lipstick: Prettier",

withYarnCache(),

bk.Cmd("dev/ci/yarn-run.sh format:check"))

}

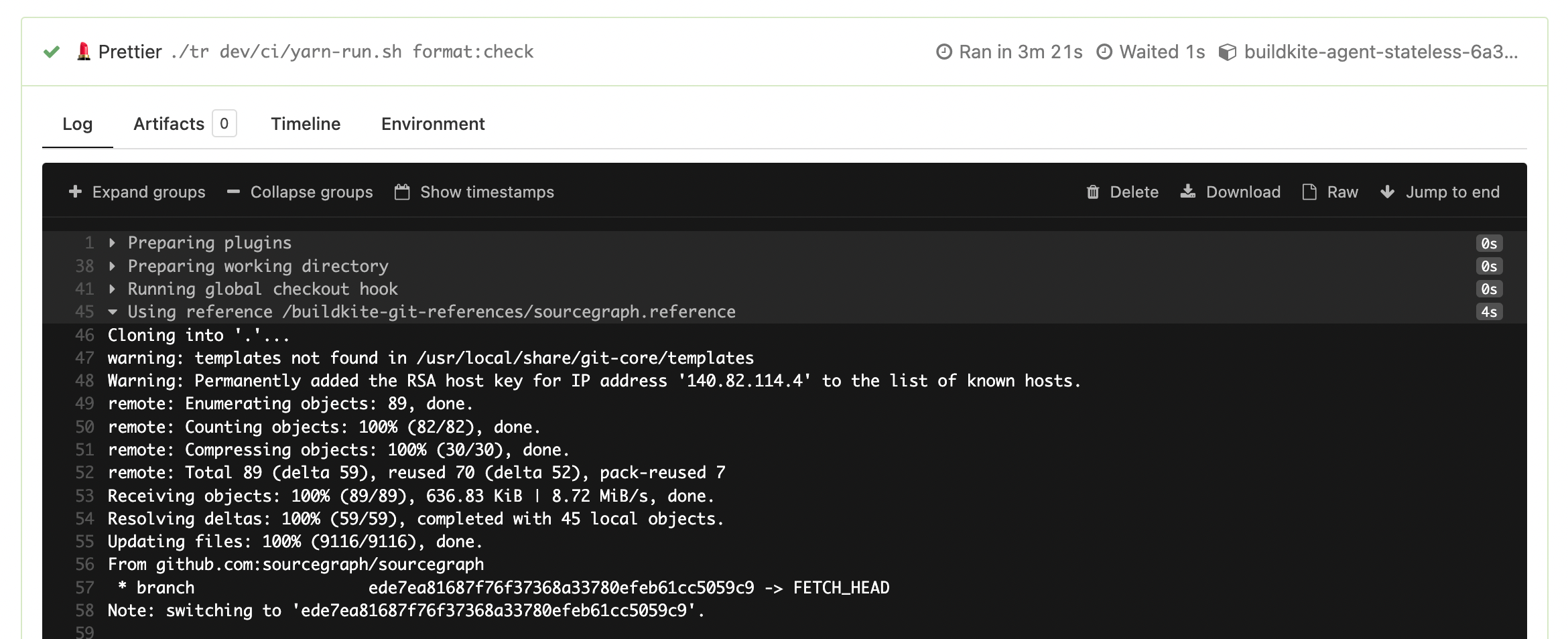

A lingering problem continued to be the initial clone step, however, especially in the main sourcegraph/sourcegraph monorepo, which can take upwards of 30 seconds to perform a shallow clone. We can’t entirely depend on shallow clones either, since our pipeline generator depends on performing diffs against our main branch to determine how to construct a pipeline. This is especially painful for short steps, where the time to run a linter check might be around the same amount of time it takes to perform a clone.

Buildkite supports a feature that allows all jobs on a single host to share a single git clone, using git clone --mirror. Subsequent clones after the initial clone can leverage the mirror repository with git clone --reference:

If the reference repository is on the local machine, […] obtain objects from the reference repository. Using an already existing repository as an alternate will require fewer objects to be copied from the repository being cloned, reducing network and local storage costs.

On our old stateless agents, this means that while some jobs can take the same 30 seconds to clone the repository, most jobs that land on “warm” agents will have a much faster clone time - roughly 5 seconds.

To recreate this feature on our stateless agents, I created a daily cron job that:

- Creates a disk in Google Cloud, with

gcloud compute disks create buildkite-git-references-"$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER" - Deploys a Kubernetes PersistentVolume and PersistentVolumeClaim corresponding to the new disk

- Deploys a Kubernetes Job that mounts the generated PersistentVolumeClaim and creates a clone mirror

- Updates the PersistentVolumeClaim to be labelled

state: ready

We generate resources to deploy using envsubst <$TEMPLATE >$GENERATED on a template spec. For example, the PersistentVolume template spec looks like:

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolume

metadata:

name: buildkite-git-references-$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER

namespace: buildkite

labels:

deploy: buildkite

for: buildkite-git-references

state: $PV_STATE

id: '$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER'

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

- ReadOnlyMany

claimRef:

name: buildkite-git-references-$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER

namespace: buildkite

gcePersistentDisk:

fsType: ext4

# the disk we created with 'gcloud compute disks create'

pdName: buildkite-git-references-$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER

capacity:

storage: 16G

persistentVolumeReclaimPolicy: Delete

storageClassName: buildkite-git-references

PersitentVolumes are created with accessModes: [ReadWriteOnce, ReadOnlyMany] - the idea is that we will mount it as ReadWriteOnce to populate the disk with a mirror repository, before allowing all our agents to mount the disk as ReadOnlyMany:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: buildkite-git-references-populate

namespace: buildkite

annotations:

description: Populates the latest buildkite-git-references disk with data.

spec:

parallelism: 1

completions: 1

ttlSecondsAfterFinished: 240 # allow us to fetch logs

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: buildkite-git-references-populate

spec:

containers:

- name: populate-references

image: alpine/git:v2.32.0

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

command: ['/bin/sh']

args:

- '-c'

# Format:

# git clone git@github.com:sourcegraph/$REPO /buildkite-git-references/$REPO.reference;

- |

mkdir /root/.ssh; cp /buildkite/.ssh/* /root/.ssh/;

git clone git@github.com:sourcegraph/sourcegraph.git \

/buildkite-git-references/sourcegraph.reference;

echo 'Done';

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /buildkite-git-references

name: buildkite-git-references

restartPolicy: OnFailure

volumes:

- name: buildkite-git-references

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: buildkite-git-references-$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER

The buildkite-job-dispatcher can now simply list all the available PersistentVolumeClaims that are ready:

var gitReferencesPVC *corev1.PersistentVolumeClaim

var listGitReferencesPVCs corev1.PersistentVolumeClaimList

if err := k8sClient.List(ctx, config.TemplateJobNamespace, &listGitReferencesPVCs,

k8s.QueryParam("labelSelector", "state=ready,for=buildkite-git-references"),

); err != nil {

runLog.Error("failed to fetch buildkite-git-references PVCs", zap.Error(err))

} else {

gitReferencesPVCs := PersistentVolumeClaims(listGitReferencesPVCs.GetItems())

pvcCount := zapMetric("pvcs", len(gitReferencesPVCs))

if len(gitReferencesPVCs) > 0 {

sort.Sort(gitReferencesPVCs)

gitReferencesPVC = gitReferencesPVCs[0]

} else {

runLog.Warn("no buildkite-git-references PVCs found", pvcCount)

}

}

And apply it to the agent Jobs we dispatch:

if gitReferencePVC != nil {

job.Spec.Template.GetSpec().Volumes = append(job.Spec.Template.GetSpec().GetVolumes(),

&corev1.Volume{

Name: stringPtr("buildkite-git-references"),

VolumeSource: &corev1.VolumeSource{

PersistentVolumeClaim: &corev1.PersistentVolumeClaimVolumeSource{

ClaimName: gitReferencePVC.GetMetadata().Name,

ReadOnly: boolPtr(true),

},

},

})

agentContainer.VolumeMounts = append(agentContainer.GetVolumeMounts(),

&corev1.VolumeMount{

Name: stringPtr("buildkite-git-references"),

ReadOnly: boolPtr(true),

MountPath: stringPtr("/buildkite-git-references"),

})

}

And that’s it! We now have repository clone times that are consistently within the 3-7 seconds range, depending on how much your branch has diverged from main. As new disks become available, newly dispatched agents will automatically leverage more up-to-date mirror repositories.

Within the same daily cron job that deploys these disks, we can also prune disks that are no longer used by any agents:

kubectl describe pvc -l for=buildkite-git-references,id!="$BUILDKITE_BUILD_NUMBER" |

grep -E "^Name:.*$|^Used By:.*$" | grep -B 2 "<none>" | grep -E "^Name:.*$" |

awk '$2 {print$2}' |

while read -r vol; do kubectl delete pvc/"${vol}" --wait=false; done

Interestingly enough, there is no way to easily detect if a PersistentVolumeClaim is completely unused. We can detect unbound disks easily, but that doesn’t mean the same thing - in this setup PersistentVolumes are always bound, even when that PersistentVolumeClaim may or may not be in use. kubectl describe has this information though1, which is what the above script (based on this StackOverflow answer) uses.

# Stateless agents

So far, we have already seen a drastic reduction in tool-related flakes in CI, and the switch to stateless agents has helped us maintain confidence that issues are related to botched state and poor isolation. There are probably other mechanisms for maintaining isolation between builds, but for our case this seemed to have the easiest migration path.

-

A quick Sourcegraph search for

"Used By"quickly reveals this line as the source of the output. A customgetPodsForPVCis the source of the pods listed here, and looking for references reveals that nokubectlcommand exposes this functionality exceptkubectl describe, so lengthy script it is! ↩