Sleuthing the web

scraping data for a bad search engine

- 24 minsMy first project at UBC Launch Pad was Sleuth. The goal of Sleuth changed quite a bit over the course of the semester but at its core we wanted it to be a search engine, geared towards UBC-related content.

This post will mostly be about the Web component’s crawling systems and how an amateur (me) approached data farming for a search engine service and indexing content in Apache Solr, a schemaless database geared towards search.

The team started out as a five-person team, but ended up being just two people, including myself, which complicated plans a bit. The bulk of our effort ended up going into our content and search components, and the front end was a bit of a tacked-on interface to demo our main “feature”: linked results.

I think it was pretty neat. Built mostly by team member Bruno, the front end is pretty clean, and featured cute, draggable nodes.

We set up Sleuth as a three-component project:

- Web: Sleuth’s API endpoints, database connections, and crawler

- Solr: our Apache Solr instance

- Frontend: Sleuth’s snazzy face

# Crawling and Scraping the Web

Content curation is handled by the sleuth_crawler (source). The crawler is based on scrapy, a popular and flexible web scraping library for Python.

In theory, the scraper needed to:

- visit a page and visit each of its links

- retrieve relevant information

- store in our database

Turns out all this is far easier said than done. Since this wasn’t just my first web scraping experience, but also my first Python experience, and everything was strange and confusing. I went through a huge number of strange and convoluted renditions of the scraper before I finally settled on a design.

It turns out there was no conceivable way to design a single crawler that would handle the seemingly infinite types of sites out there. Perhaps this is a bit obvious, but for a long time I was trying to come up with a “definition” that my crawler could rely on every website to have, and attempt to retrieve information that way. That did not work very well.

Fun fact - Google itself seems to cheat a bit on this by offering the Google Search Console! Here you can request hits from the Google crawler and find out how to add “rich results” for your web page. You do this by using specific metadata tags that Google’s crawler can look for and retrieve. Turns out Google’s nice search result “cards” aren’t as magical as I thought they were… although it is still very neat.

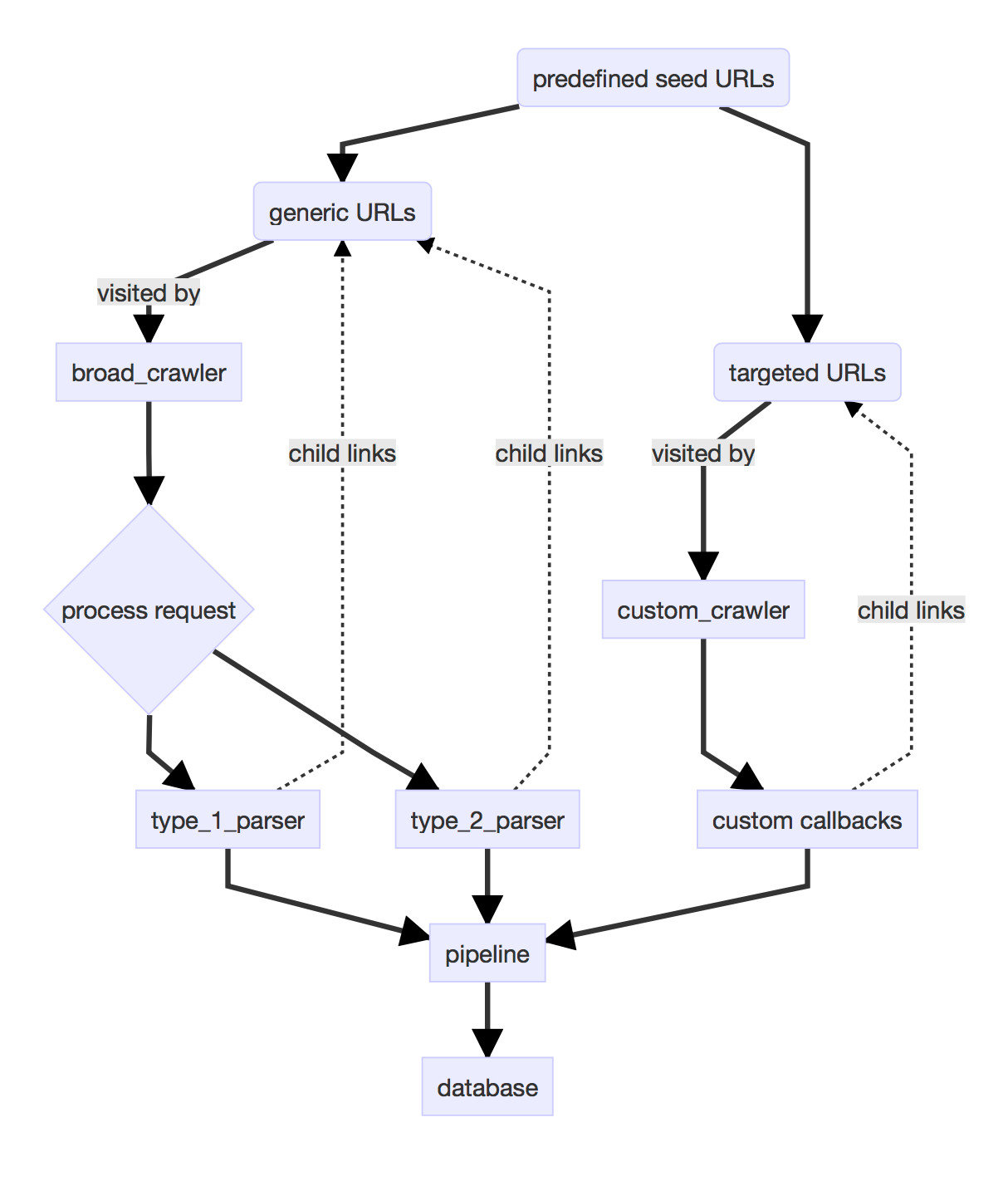

We didn’t have the search presence of Google leverage when asking people to conform to our crawler’s expectations, so I focused on defining a number of categories. On the top level, I set up two crawlers: a broad_crawler that would generically traverse the links in its source pages, and a custom_crawler that would take a custom parser module to handle crawling. A crawler is essentially a bot that would visit and retrieve data from sites. These crawlers would then identify and pass web pages to the appropriate parsers. The data flow looks a bit like this:

# Parsers

I placed different parsers for different page types in a folder together in /scraper/spiders/parsers (source). I relied heavily on xpath to query for elements I wanted.

We also set up a few “datatypes” that would represent our web pages and what kind of data we wanted to retrieve:

class ScrapyGenericPage(scrapy.Item):

'''

Stores generic page data and url

'''

url = scrapy.Field()

title = scrapy.Field()

site_title = scrapy.Field()

description = scrapy.Field()

raw_content = scrapy.Field()

links = scrapy.Field()

There are a wide variety of tags to rely on for most pages. For our “generic” pages, I didn’t need to get too in depth - some simple descriptive metadata would be sufficient.

def parse_generic_item(response, links):

'''

Scrape generic page

'''

title = utils.extract_element(response.xpath("//title/text()"), 0).strip()

titles = re.split(r'\| | - ', title)

# Use OpenGraph title data if available

if len(response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:site_name"]')) > 0 and \

len(response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:title"]')) > 0:

title = utils.extract_element(

response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:title"]/@content'), 0

)

site_title = utils.extract_element(

response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:site_name"]/@content'), 0

)

elif len(titles) >= 2:

title = titles[0].strip()

site_titles = []

for i in range(max(1, len(titles)-2), len(titles)):

site_titles.append(titles[i].strip())

site_title = ' - '.join(site_titles)

else:

site_title = ''

# Use OpenGraph description if available

if len(response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:description"]')) > 0:

desc = utils.extract_element(

response.xpath('//meta[@property="og:description"]/@content'), 0

)

else:

desc = utils.extract_element(

response.xpath('//meta[@name="description"]/@content'), 0

)

raw_content = utils.strip_content(response.body)

return ScrapyGenericPage(

url=response.url,

title=title,

site_title=site_title,

description=desc,

raw_content=raw_content,

links=links

)

I think there are probably a few other metadata systems besides OpenGraph that can be leveraged for interesting metadata, though I only got around to implementing one. Again, xpath was my friend here - I used Chrome’s inspector to quickly pick out xpath elements I needed.

For more specific types I could get a bit more in-depth. For example, for Reddit posts, I could make post parsing dependent on karma, and retrieve comments above a certain karma threshold as well.

def parse_post(response, links):

'''

Parses a reddit post's comment section

'''

post_section = response.xpath('//*[@id="siteTable"]')

# check karma and discard if below post threshold

karma = utils.extract_element(

post_section.xpath('//div/div/div[@class="score unvoted"]/text()'), 0

)

if karma == "" or int(karma) < POST_KARMA_THRESHOLD:

return

# get post content

post_content = utils.extract_element(

post_section.xpath('//div/div[@class="entry unvoted"]/div/form/div/div'), 0

)

post_content = utils.strip_content(post_content)

# get post title

titles = utils.extract_element(response.xpath('//title/text()'), 0)

titles = titles.rsplit(':', 1)

title = titles[0].strip()

subreddit = titles[1].strip()

# get comments

comments = []

comment_section = response.xpath('/html/body/div[4]/div[2]')

comment_section = comment_section.xpath('//div/div[@class="entry unvoted"]/form/div/div')

for comment in comment_section:

comment = utils.strip_content(comment.extract())

if len(comment) > 0:

comments.append(' '.join(c for c in comment))

return ScrapyRedditPost(

url=response.url,

title=title,

subreddit=subreddit,

post_content=post_content,

comments=comments,

links=links

)

Each parser creates a Scrapy item (in this case, a ScrapyRedditPost) and populates its fields with the data retrieved from crawled page. Which was easier said than done - retrieving Reddit elements was far, far more complicated than I had expected - notice how damned nested the pathing gets:

# get post content

post_content = utils.extract_element(

# div div div div div div div for days

post_section.xpath('//div/div[@class="entry unvoted"]/div/form/div/div'), 0

)

The inspector didn’t help too much. I ended up manually counting how many nested divs there were for each element I wanted, and saved an entire page to run tests on. Perhaps the Reddit API might have been easier, but I wanted to form “links” between Reddit pages and normal websites when displaying results on the Sleuth frontend - I felt that parsing Reddit as standard web pages would be the most organic way to achieve this.

To test my parsers and avoid trial and erroring my way through, I saved sample pages as text documents (instead of HTML, since that was throwing off our GitHub language statistics) and built a small helper function to deliver a mock response to a parser:

from scrapy.http import Request, TextResponse

def mock_response(file_name=None, url='https://www.ubc.ca'):

'''

Create a fake Scrapy HTTP response

file_name can be a relative file path or the desired contents of the mock

'''

request = Request(url=url)

if file_name:

try:

file_path = "sleuth_crawler/tests" + file_name

file_content = open(file_path, 'r').read()

except OSError:

file_content = ""

else:

file_content = ""

return TextResponse(

url=url,

request=request,

body=file_content,

encoding='utf-8'

)

TextResponse is one of Scrapy’s response classes, where a response is the result of a visiting a page. This mock response can be given to a parser to test, like so:

class TestGenericPageParser(TestCase):

def test_parse_text_post(self):

'''

Test parsing a reddit text post

'''

response = mock_response('/test_data/reddit_text_post.txt', 'https://www.reddit.com/')

links = ['https://www.google.com', 'https://www.reddit.com']

item = parser.parse_post(response, links)

item = ScrapyRedditPost(item)

self.assertEqual('UBC', item['subreddit'])

self.assertEqual(

"As a first year student it's really hard to get into the UBC discord",

item['title']

)

self.assertEqual(

"Don't worry, it feels like that for everyone.At some point, the UBC discord became it's own little circle-jerk of friends, exclusive to anyone else. There are about 8-10 regular users, who communicate mainly through inside jokes and 4chan-esque internet humour. You're better off without them, I guarantee.",

item['comments'][0]

)

def test_karma_fail(self):

'''

Test if the parser discards low-karma or no-karma posts

'''

response = mock_response() # this should have no karma because it's empty!

item = parser.parse_post(response, [])

self.assertFalse(item)

This was a huge help for me, and probably saved me a crazy amount of time, since I could rapidly iterate on my parser design by running them against various sample texts. The tests can be found here.

# Crawlers

I made this distinction between a broad_crawler and a custom_crawler because UBC course data had to be crawled in a very specific manner from the UBC course site, and we wanted to be able to retrieve very specific information (such as rows of tables on the page for course section data). The idea was that custom_crawler would be an easily extendable module that could be used to target specific sites. Because of this, the course_crawler itself was pretty simple:

import scrapy

from scrapy.spiders import Spider

class CustomCrawler(Spider):

'''

Spider that crawls specific domains for specific item types

that don't link to genericItem

'''

name = 'custom_crawler'

def __init__(self, start_urls, parser):

'''

Takes a list of starting urls and a callback for each link visited

'''

self.start_urls = start_urls

self.parse = parser

To start it up, I would attach the appropriate parsing module to the crawler and let it run free:

process.crawl('custom_crawler', start_urls=CUSTOM_URLS['courseItem'], parser=parse_subjects)

The broad_crawler is where the modularised parser design really shined, I think, allowing me to dynamically assign parsers after processing each request. I also set up some very rudimentary filtering when retrieving a page’s links.

class BroadCrawler(CrawlSpider):

'''

Spider that broad crawls starting at list of predefined URLs

'''

name = 'broad_crawler'

# These are the links that the crawler starts crawling at

start_urls = PARENT_URLS

# Rules for what links are followed are defined here

allowed_terms = [r'(ubc)', r'(university)', r'(ubyssey)', r'(prof)', r'(student)', r'(faculty)']

denied_terms = [r'(accounts\.google)', r'(intent)', r'(lang=)']

GENERIC_LINK_EXTRACTOR = LinkExtractor(allow=allowed_terms, deny=denied_terms)

rules = (

Rule(

GENERIC_LINK_EXTRACTOR,

follow=True, process_request='process_request',

callback='parse_generic_item'

),

)

def process_request(self, req):

'''

Assigns best callback for each request

'''

if 'reddit.com' in req.url:

req = req.replace(priority=100)

if 'comments' in req.url:

req = req.replace(callback=self.parse_reddit_post)

else:

req = req.replace(callback=self.no_parse)

return req

A lot of this is build using many of Scrapy’s built-in features - me explaining them is not going to be anywhere near as good as documentation, so I’m just going to recommend really studying that if you want to get in-depth into some of Scrapy’s many wild features.

# Performance

Performance is pretty important when it comes to web crawling for a search engine. The more data you have on store, the higher the chances that you will have good, interesting results. For us, more data also meant more links, which was the foundation of how we wanted our data to be displayed on the Sleuth frontend.

In the interest of that, I made a few tweaks to the Scrapy settings and pipelines. I will go over the pipeline in the next section. These two areas were more or less the only places I could realistically make optimizations - we didn’t have the time, skill or resources to set up systems like distributed crawling, so we stuck with the basics.

The first thing I wanted to change was depth priority. Because we start with a few seed URLs (scroll back up to the flowchart for a reminder), I didn’t want Scrapy to spend all our system resources chasing links from the first seed URL, so I reduced the depth priority so that the crawlers would be able to get a greater “breadth” or results from a wider range of sources.

# Process lower depth requests first

DEPTH_PRIORITY = 50

I also allowed Scrapy to abuse my laptop for resources:

# Configure maximum concurrent requests performed by Scrapy (default: 16)

CONCURRENT_REQUESTS = 100

# Increase max thread pool size for DNS queries

REACTOR_THREADPOOL_MAXSIZE = 20

And I disabled a few things that might slow down site visits:

# Disobey robots.txt rules - sorry!

ROBOTSTXT_OBEY = False

# Reduce download timeout to discard stuck requests quickly

DOWNLOAD_TIMEOUT = 15

# Built-in Logging Level (alternatively use DEBUG outside production)

LOG_LEVEL = 'INFO'

# Disable cookies (enabled by default)

COOKIES_ENABLED = False

As far as crawling manners go (yes, there seems to be crawling manners! Scrapy includes a “crawl responsibly” message on its default settings), this is pretty rude. But oh well! Sorry site admins.

# Pipeline

Scrapy makes it easy to scaffold a pipeline for handling all the data that comes through its scrapers. However, since data assembly was already being managed by the parsers, all Sleuth’s pipeline had to do was send data coming through off to the database.

This was done through a custom Solr interface we built on top of pysolr, a Solr driver for Django.

This allowed us to tack on some additional optimizations and customizations, namely our database design - where each “core” is a consistent schema for a particular datatype - and insertion queing. Insertion queing drastically reduced the bottleneck we were seeing at the pipeline, where the crawlers were processing data far faster than the connection interface could handle. You can see the full source of the interface here, but here’s some of the more relevant bits:

class SolrConnection(object):

'''

Connection to Solr database

'''

# The number of documents held in a core's insert queue before

# the documents in the core are automatically inserted.

QUEUE_THRESHOLD = 100

def __init__(self, url):

'''

Creates a SolrConnection form the given base Solr url of the form

'https://<solrhostname>:<port>/solr'.

'''

self.url = url

self.solr = pysolr.Solr(url, timeout=10)

self.solr_admin = pysolr.SolrCoreAdmin(url + '/admin/cores')

self.cores = {}

self.queues = {}

for core_name in self.fetch_core_names():

self.cores[core_name] = pysolr.Solr(self.url + '/' + core_name)

self.queues[core_name] = list()

def queue_document(self, core, doc):

'''

Queues a document for insertion into the specified core and returns None.

If the number of documents in the queue exceeds a certain threshold,

this function will insert them all the documents held in the queue of the

specified core and return the response from Solr.

All values in 'doc' must be strings.

'''

if core not in self.cores:

raise ValueError("A core for the document type {} was not found".format(core))

self.queues[core].append(doc)

if len(self.queues[core]) >= self.QUEUE_THRESHOLD:

docs = list(self.queues[core].copy())

del self.queues[core][:]

return self.insert_documents(core, docs)

return None

def insert_queued(self):

'''

Inserts all queued documents across all cores. Returns an object

containing the Solr response from each core.

'''

response = {}

for core in self.cores:

docs = list(self.queues[core].copy())

del self.queues[core][:]

response[core] = self.insert_documents(core, docs)

return response

This connection is opened and closed by the pipeline as needed:

from sleuth_backend.views.views import SOLR

class SolrPipeline(object):

'''

Process item and store in Solr

'''

def __init__(self, solr_connection=SOLR):

self.solr_connection = solr_connection

def close_spider(self, spider=None):

'''

Defragment Solr database after spider completes task and

insert any queued documents.

'''

self.solr_connection.insert_queued()

self.solr_connection.optimize()

I allowed optional parameters so that I could easily inject the connection dependencies for tests using Python’s ABSOLUTELY AMAZINGLY MAGICAL MagicMock and patch. Seriously these utilities are amazing, although I was absolutely spoiled by it - it made testing in any other language feel like a pain. You’ve been warned.

@patch('sleuth_backend.solr.connection.SolrConnection')

def setUp(self, fake_solr):

self.fake_solr = fake_solr

self.pipeline = SolrPipeline(solr_connection=fake_solr)

MagicMock sets up a mock object that has all the functions of fake_solr, except that they do nothing when called, and this mock object can then easily be injected into the pipeline to run tests.

Back to the pipeline - it receives all the ScrapyItems returned from the crawlers and converts them to our Solr models, and calls a function that queues the given document for insertion.

def process_item(self, item, spider=None):

'''

Match item type to predefined Schemas

'''

if isinstance(item, ScrapyGenericPage):

self.__process_generic_page(item)

elif isinstance(item, ScrapyCourseItem):

self.__process_course_item(item)

elif isinstance(item, ScrapyRedditPost):

self.__process_reddit_post(item)

return item

def __process_generic_page(self, item):

'''

Convert Scrapy item to Solr GenericPage and queues it for insertion

'''

solr_doc = GenericPage(

id=item["url"],

type="genericPage",

name=item["title"],

siteName=item["site_title"],

updatedAt=self.__make_date(),

content=self.__parse_content(item["raw_content"]),

description=item["description"],

links=item["links"]

)

solr_doc.save_to_solr(self.solr_connection)

The Solr models simply define the fields of each data type - essentially the schema of each Solr “core”, since Solr is a schemaless database. They all extend a superclass we made, and all it really does is sets up and inserts an object to our database. This is also where I learned about **kwargs trickeries, which has come in very handy for me. Designed mostly by Bruno, this setup is also what inspired the polymorphic datatypes I use at work.

class SolrDocument(object):

'''

An base class for documents that are inserted into Solr, an retured as

search results from the Sleuth API.

'''

# Default doc fields: all subtypes must at least have these fields

doc = {

"id": "",

"type": "",

"name": "",

"updatedAt": "",

"description": ""

}

def __init__(self, doc, **kwargs):

'''

This method should be called by the subclass constructor.

'''

self.doc = doc

for key in self.doc.keys():

if key in kwargs and key is not 'type':

doc[key] = kwargs[key]

def save_to_solr(self, solr_connection):

'''

Submits the document to the given Solr connection.

'''

solr_connection.queue_document(self.type(), self.doc.copy())

class GenericPage(SolrDocument):

# doc is the type definition

doc = {

"id": "",

"type": "genericPage",

"name": "",

"updatedAt": "",

"siteName": "",

"description": "",

"content": "",

"links": []

}

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

super(GenericPage, self).__init__(self.doc, **kwargs)

And tada! Now running our crawlers rapidly populates our database with beautiful data. Data data data. Coming soon(tm) in another post: Sleuth’s search APIs and how it works. Stay tuned!